Welcome to the Virtual Education Wiki ~ Open Education Wiki

Japan

by Paul Bacsich (Sero), Terumi Miyazoe (Open University of Japan), and Daniela Proli (SCIENTER)

For entities in Japan see Category:Japan

Partners and experts in Japan

There is no partner in Japan for Re.ViCa, VISCED or POERUP. We would love these and more to make direct contributions to updating this Re.ViCa/VISCED page and to the POERUP Japan page at http://poerup.referata.com/wiki/Japan

Japan in a nutshell

(sourced from Wikipedia)

Japan (日本 Nihon or Nippon?, officially 日本国 Nippon-koku?·i or Nihon-koku) is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, People's Republic of China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south. The characters which make up Japan's name mean "sun-origin country", which is why Japan is sometimes identified as the "Land of the Rising Sun".

Japan comprises over 3,000 islands making it an archipelago. The largest islands are Honshū, Hokkaidō, Kyūshū and Shikoku, together accounting for 97% of Japan's land area. Most of the islands are mountainous, many volcanic; for example, Japan’s highest peak, Mount Fuji, is a volcano. Japan has the world's tenth largest population, with about 128 million people. The Greater Tokyo Area, which includes the de facto capital city of Tokyo and several surrounding prefectures, is the largest metropolitan area in the world, with over 30 million residents.

A major economic power, Japan has the world's second largest economy by nominal GDP and the third largest in purchasing power parity. It is a member of the United Nations, G8, G4, OECD and APEC, with the world's fifth largest defense budget. It is also the world's fourth largest exporter and sixth largest importer. It is a developed country with high living standards (8th highest HDI) and a world leader in technology, machinery, and robotics.

The English word Japan is an exonym. The Japanese names for Japan are Nippon (にっぽん) and Nihon (にほん). They are both written in Japanese using the kanji 日本. The Japanese name Nippon is used for most official purposes, including on Japanese money, postage stamps, and for many international sporting events. Nihon is a more casual term and the most frequently used in contemporary speech.

Both Nippon and Nihon literally mean "the sun's origin" and are often translated as the Land of the Rising Sun. This nomenclature comes from Imperial correspondence with Chinese Sui Dynasty and refers to Japan's eastward position relative to China. Before Japan had relations with China, it was known as Yamato and Hi no moto, which means "source of the sun".

Japan is a constitutional monarchy where the power of the Emperor is very limited. As a ceremonial figurehead, he is defined by the constitution as "the symbol of the state and of the unity of the people". Power is held chiefly by the Prime Minister of Japan and other elected members of the Diet, while sovereignty is vested in the Japanese people. The Emperor effectively acts as the head of state on diplomatic occasions. Akihito is the current Emperor of Japan. Naruhito, Crown Prince of Japan, stands as next in line to the throne.

Japan's legislative organ is the National Diet, a bicameral parliament. The Diet consists of a House of Representatives, containing 480 seats, elected by popular vote every four years or when dissolved and a House of Councillors of 242 seats, whose popularly-elected members serve six-year terms. There is universal suffrage for adults over 20 years of age, with a secret ballot for all elective offices.

The Prime Minister of Japan is the head of government. The position is appointed by the Emperor of Japan after being designated by the Diet from among its members and must enjoy the confidence of the House of Representatives to remain in office. The Prime Minister is the head of the Cabinet (the literal translation of his Japanese title is "Prime Minister of the Cabinet") and appoints and dismisses the Ministers of State, a majority of whom must be Diet members.

While there exist eight commonly defined regions of Japan, administratively Japan consists of forty-seven prefectures, each overseen by an elected governor, legislature and administrative bureaucracy. The former city of Tokyo is further divided into twenty-three special wards, each with the same powers as cities.

The nation is currently undergoing administrative reorganization by merging many of the cities, towns and villages with each other. This process will reduce the number of sub-prefecture administrative regions and is expected to cut administrative costs.

Japan has dozens of major cities, which play an important role in Japan's culture, heritage and economy.

Japan's population is estimated at just over 127 million. For the most part, Japanese society is linguistically and culturally homogeneous with small populations of foreign workers, Zainichi Koreans, Zainichi Chinese, Filipinos, Japanese Brazilians and others. The most dominant native ethnic group is the Yamato people; the primary minority groups include the indigenous Ainu and Ryukyuan, as well as social minority groups like the burakumin.

Japan has one of the highest life expectancy rates in the world, at 81.25 years of age as of 2006. The Japanese population is rapidly aging, the effect of a post-war baby boom followed by a decrease in births in the latter part of the twentieth century. In 2004, about 19.5% of the population was over the age of 65.

The changes in the demographic structure have created a number of social issues, particularly a potential decline in the workforce population and increases in the cost of social security benefits such as the public pension plan. Many Japanese youth are increasingly preferring not to marry or have families as adults. Japan's population is expected to drop to 100 million by 2050 and to 64 million by 2100. Demographers and government planners are currently in a heated debate over how to cope with this problem. Immigration and birth incentives are sometimes suggested as a solution to provide younger workers to support the nation's aging population. The highest estimates for the amount of Buddhists and Shintoists in Japan is 84-96%, representing a large number of believers in a syncretism of both religions. However, these estimates are based on people with an association with a temple, rather than the number of people truly following the religion. Professor Robert Kisala (Nanzan University) suggests that only 30 percent of the population identify themselves as belonging to a religion.

Taoism and Confucianism from China have also influenced Japanese beliefs and customs. Religion in Japan tends to be syncretic in nature, and this results in a variety of practices, such as parents and children celebrating Shinto rituals, students praying before exams, couples holding a wedding at a Christian church and funerals being held at Buddhist temples. A minority (2,595,397, or 2.04%) profess to Christianity. In addition, since the mid-19th century, numerous religious sects (Shinshūkyō) have emerged in Japan, such as Tenrikyo and Aum Shinrikyo (or Aleph).

About 99% of the population speaks Japanese as their first language. It is an agglutinative language distinguished by a system of honorifics reflecting the hierarchical nature of Japanese society, with verb forms and particular vocabulary which indicate the relative status of speaker and listener. According to a Japanese dictionary Shinsen-kokugojiten, Chinese-based words comprise 49.1% of the total vocabulary, indigenous words are 33.8% and other loanwords are 8.8%. The writing system uses kanji (Chinese characters) and two sets of kana (syllabaries based on simplified Chinese characters), as well as the Latin alphabet and Arabic numerals. The Ryukyuan languages, also part of the Japonic language family to which Japanese belongs, are spoken in Okinawa, but few children learn these languages. The Ainu language is moribund, with only a few elderly native speakers remaining in Hokkaidō. Most public and private schools require students to take courses in both Japanese and English.

Education in Japan

Policy

Primary, secondary schools and universities were introduced into Japan in 1872 as a result of the Meiji Restoration. Since 1947, compulsory education in Japan consists of elementary school and middle school, which lasts for nine years (from age 6 to age 15). Almost all children continue their education at a three-year senior high school, and, according to the Ministry, about 75.9% of high school graduates attend a university, junior college, trade school, or other post-secondary institution in 2005.

Japan's education is very competitive, especially for entrance to institutions of higher education. Anyone can enter one nowadays.

The two top-ranking universities in Japan are the University of Tokyo and Kyoto University. The Programme for International Student Assessment coordinated by the OECD, currently ranks Japanese knowledge and skills of 15-year-olds as the 6th best in the world.

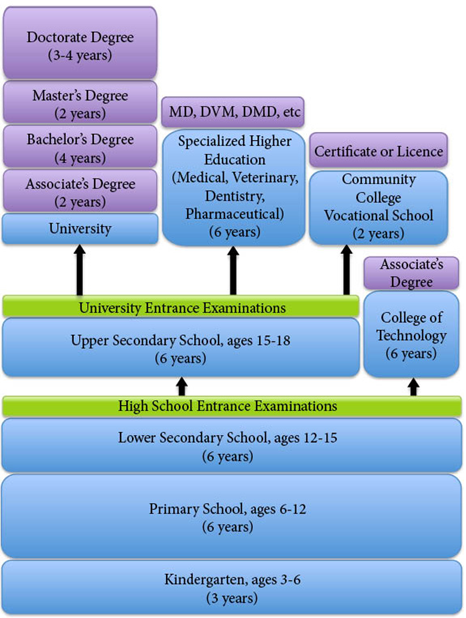

Japan education system

(sourced from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Education_in_Japan)

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the methods and structures of Western learning were adopted as a means to make Japan a strong, modern nation. Students and even high-ranking government officials were sent abroad to study, such as the Iwakura mission. Foreign scholars, the so-called o-yatoi gaikokujin, were invited to teach at newly founded universities and military academies. Compulsory education was introduced, mainly after the Prussian model. By 1890, only 20 years after the resumption of full international relations, Japan discontinued employment of the foreign consultants.

The rise of militarism led to the use of the education system to prepare the nation for war. The military even sent its own instructors to schools. After the defeat in World War II, the allied occupation government set an education reform as one of its primary goals, to eradicate militarist teachings and "democratize" Japan. The education system was rebuilt after the American model.

The end of the 1960s were a time of student protests around the world, and also in Japan. The main subject of protest was the Japan-U.S. security treaty. A number of reforms were carried out in the post-war period until today. They aimed at easing the burden of entrance examinations, promoting internationalization and information technologies, diversifying education and supporting lifelong learning.

In Japan education is compulsory for nine years, including primary school (six years) and lower secondary school (three years). Pupils can attend three years of non-compulsory kindergarten.

Students who have completed lower secondary school, at about age sixteen, may choose to apply to upper secondary school, lasting three years.

There are three types of upper secondary schools in Japan:

- senior high schools. Senior high schools provide general, specialized and integrated courses. General courses are intended for students who hope to attend university, or for students who wish to seek employment after high school but have no particular vocational preference. Specialized courses are for students who have selected a particular vocational area of interest. Integrated courses allow a student to choose electives from both the general and specialized tracks.

Senior high school can be full-time, part-time or correspondence.

- Colleges of technology (Kosen colleges) typically offer a five-year program in different occupational areas. Students can also choose to complete upper secondary vocational education after three years and go directly to the workplace. Upon graduation, a student who completes five years of technology college is considered an “associate” in his or her field.

- special training colleges for lower secondary graduates: special training colleges have been created in Japan in 1976, offering vocational and specialized technical education aiming at fostering abilities required for vocational or daily life or provide general education. Some special training colleges address people with lower secondary education, whereas two other categories are for people with upper secondary education Special training colleges offer vocational and technical education in a variety of degree programs, typically through the bachelor’s or master’s level) or for people without any academic background.

Admission into senior high schools is extremely competitive, and in addition to entrance examinations, the student’s academic work, behavior and attitude, and record of participation in the community is also taken into account. Senior high schools are ranked in each locality, and Japanese students consider the senior high school where they matriculate to be a determining factor in later success. Following senior high school, a Japanese student’s future is dependent on their score on the national achievement exam, as well as their performance on the individual exams administered by each university.

Colleges of technology require their own set of entrance exams, while special training colleges do not. After three years in a special training college, students may apply to enter a college of technology. These students are eligible for higher education after completing an upper secondary course of two to three years.

Schools in Japan

Kindergarten and Nursery school

Early childhood education begins at home, and there are numerous books and television shows aimed at helping mothers of pre-school children to educate their children and to "parent" more effectively. Much of the home training is devoted to teaching manners, proper social behavior, and structured play, although verbal and number skills are also popular themes. Parents are strongly committed to early education and frequently enroll their children in preschools.

Kindergartens (yochien 幼稚園), predominantly staffed by young female junior college graduates, are supervised by the Ministry of Education, but are not part of the official education system. The 58% of kindergartens that are private accounted for 77% of all children enrolled. In addition to kindergartens there exists a well-developed system of government-supervised day-care centers (hoikuen 保育園), supervised by the Ministry of Labor. Where as kindergartens follow educational aims, preschools are predominately concerned with providing care for infants and toddlers. Same as kindergartens there are public or privately run preschools. Together, these two kinds of institutions enroll well over 90% of all preschoolage children prior to their entrance into the formal system at first grade. The Ministry of Education's 1990 Course of Study for Preschools, which applies to both kinds of institutions, covers such areas as human relationships, environment, words (language), and expression. Starting from March 2008 the new revision of curriculum guidelines for kindergartens as well as for preschools came into effect.

Elementary school

More than 99% of children are enrolled in elementary school. All children enter first grade at age six, and starting school is considered a very important event in a child's life.

Virtually all elementary education takes place in public schools; less than 1% of the schools are private. Private schools tended to be costly, although the rate of cost increases in tuition for these schools had slowed in the 1980s. Some private elementary schools are prestigious, and they serve as a first step to higher-level private schools with which they are affiliated, and thence to a university.

Junior high school

Lower secondary school covers grades seven, eight, and nine, children between the ages of roughly 12 and 15, with increased focus on academic studies. Although it is still possible to leave the formal education system after completing lower secondary school and find employment, fewer than 4% did so by the late 1980s.

Like elementary schools, most lower-secondary schools in the 1980s were public, but 5% were private. Private schools were costly, averaging 558,592 yen (US$3,989) per student in 1988, about four times more than the 130,828 yen (US$934) that the ministry estimated as the cost for students enrolled in public lower secondary schools. Teachers often majored in the subjects they taught, and more than 80% graduated from a four-year college. Classes are large, with thirty-eight students per class on average, and each class is assigned a homeroom teacher who doubles as counselor. Unlike elementary students, lower-secondary school students have different teachers for different subjects. The teacher, however, rather than the students, moves to a new room for each fifty-minute period.

Instruction in lower-secondary schools tends to rely on the lecture method. Teachers also use other media, such as television and radio, and there is some laboratory work. By 1989 about 45% of all public lower secondary schools had computers, including schools that used them only for administrative purposes. Classroom organization is still based on small work groups, although no longer for reasons of discipline.

All course contents are specified in the Course of Study for Lower-Secondary Schools. Some subjects, such as Japanese language and mathematics, are coordinated with the elementary curriculum. Others, such as foreign-language study, usually English, begin at this level. The curriculum covers Japanese language, social studies, mathematics, science, music, fine arts, health, and physical education. All students also are exposed to either industrial arts or homemaking. Moral education and special activities continue to receive attention. Many students also participate in after-school sport clubs that occupy them until around 6pm most weekdays.

A growing number of JHS students also attend Juku, private extracurricular study schools, in the evenings and weekends. A focus by students upon these other studies and the increasingly structured demands upon students' time have been criticized by teachers and in the media for contributing to a decline in classroom standards and student performance in recent years.

The ministry recognizes a need to improve the teaching of all foreign languages, especially English. To improve instruction in spoken English, the government invites many young native speakers of English to Japan to serve as assistants to school boards and prefectures under its Japan Exchange and Teaching Program. By 1988 participants numbered over 1,000. This program seems to be being phased out in many areas where the supply of foreign native speakers facilitates their employment through less expensive private agencies.

(Senior) High school

Even though upper secondary school is not compulsory in Japan, 99% of all lower secondary school graduates entered upper secondary schools as of 2005. Private upper-secondary schools account for about 55% of all upper-secondary schools, and neither public nor private schools are free . The Ministry of education estimated that annual family expenses for the education of a child in a public upper-secondary school were about 300,000 yen (US$2,142) in both 1980s and that private upper-secondary schools were about twice as expensive.

The most common type of upper-secondary schools has a fulltime, general program that offered academic courses for students preparing for higher education and also technical and vocational courses for students expecting to find employment after graduation. More than 70% of upper-secondary school students were enrolled in the general academic program in the late 1980s. A small number of schools offer part-time or evening courses or correspondence education.

The first-year programs for students in both academic and commercial courses are similar. They include basic academic courses, such as Japanese language, English, mathematics, and science. In upper-secondary school, differences in ability are first publicly acknowledged, and course content and course selection are far more individualized in the second year. However, there is a core of academic material throughout all programs.

Vocational-technical programs includes several hundred specialized courses, such as information processing, navigation, fish farming, business English, and ceramics. Business and industrial courses are the most popular, accounting for 72% of all students in full-time vocational programs in 1989.

Most upper-secondary teachers are university graduates. Uppersecondary schools are organized into departments, and teachers specialize in their major fields although they teach a variety of courses within their disciplines. Teaching depends largely on the lecture system, with the main goal of covering the very demanding curriculum in the time allotted. Approach and subject coverage tends to be uniform, at least in the public schools.

Training of disabled students, particularly at the uppersecondary level, emphasizes vocational education to enable students to be as independent as possible within society.

Vocational training varies considerably depending on the student's disability, but the options are limited for some. It is clear that the government is aware of the necessity of broadening the range of possibilities for these students. Advancement to higher education is also a goal of the government, and it struggles to have institutions of higher learning accept more disabled students.

Further and Higher education

After the Second World War, Japan has moved rapidly from an “elite” to a “mass” higher education system and the rapid expansion in both the number and the size of Japanese universities has also witnessed the introduction of a trend towards more “vocational” degree programmes - i.e. ones which offer more of a fit-for-purpose licence to engage in professional practice. Thus the expansion of tertiary education has been accompanied by increasing diversity in the mission and purposes of tertiary institutions, both within and between those categories outlined above. The cultivation of such mission diversity is now a stated policy aim.

Interestingly, Japan has traditionally blurred the distinction between further and higher education, whilst retaining a degree of distinctiveness between vocational and academic programs and qualifications. This has favored the flourishing of the college sector, offering post-18 sub-bachelor qualification. Many junior colleges are vocationally-oriented but also with a strong liberal-arts component.

Tertiary Education in Japan comprises the following

- Universities have as their aim to conduct teaching and research in depth in specialised academic subjects, to operate as “centres of learning” and to “develop intellectual, moral and practical abilities”.

- Junior colleges “cultivate such abilities as are required in vocation or practical life”, typically offering two-year sub-degree qualifications within a baccalaureate four-year bachelor’s degree framework. There are typically progression opportunities to

university programmes. The School Education Act was partially amended in 2005, and associate degrees came to be awarded to graduates of Japanese junior colleges.

- Colleges of technology, or kosen are institutions offering high-level vocational qualifications through teaching and related research. They are organized through the Institute of National Colleges of Technology and offer vocational education for those between the ages of 15 and 20, with the possibility of “topping-up” to a full degree

- Professional training colleges offer practical vocational and specialized technical education aiming to foster abilities required for vocational or daily life, or provide general education.

- Graduate schools conduct academic research, in particular basic research, and train researchers and professionals with advanced skills.

- Professional graduate schools are oriented towards high-level graduate entry to key professions - for example, law, business studies, etc.

Number of Tertiary education institutions

Universities in Japan

(sourced from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Higher_education_in_Japan - which may not be up to date)

University Entrance

College entrance is based largely on the scores that students achieved in entrance examinations (nyūgaku shiken or 入学試験). With exceptions, the public national universities are the most highly regarded. This distinction had its origins in historical factors -- the long years of dominance of the select imperial universities, such as Tokyo and Kyoto universities, which trained Japan's leaders before the war -- and in differences in quality, particularly in government subsidy. In addition, certain prestigious employers, notably the government and select large corporations, continue to restrict their hiring of new employees to graduates of the most esteemed universities. There is a close link between university background and employment opportunity;however, this has started to change because of the urgent need to cope with ever accelerating globalization and internationalization of its economy and social structure.

Students applying to national universities take two entrance examinations, first a nationally administered uniform achievement test and then an examination administered by the university that the student hopes to enter. Applicants to private universities need to take only the university's examination. Some national schools have so many applicants that they use the first test, the Joint First Stage Achievement Test, as a screening device for qualification to their own admissions test.

An unsuccessful student, who could not compete successfully for admission to the college of their choice, can either accept an admission elsewhere, forego a college education, or wait until the following spring to take the national examinations again. These students who chose the second option, called ronin or 浪人, meaning masterless samurai, spend an entire year, and sometimes longer, studying for another attempt at the entrance examinations.

Yobiko or 予備校 are private schools that, like many juku or 塾, help students prepare for entrance examinations. While yobiko have many programs for upper-secondary school students, they are best known for their specially designed full-time, year-long classes for ronin.

The number of applicants to four-year universities totaled almost 560,000 in 1988. Ronin accounted for about 40% of new entrants to four-year colleges in 1988. Most ronin were men, but about 14% were women. The ronin experience is so common in Japan that the Japanese education structure is often said to have an extra ronin year built into it. -- need update

Yobiko sponsor a variety of programs, both full-time and part-time, and employ an extremely sophisticated battery of tests, student counseling sessions, and examination analysis to supplement their classroom instruction. The cost of yobiko education is high, comparable to first-year university expenses, and some specialized courses at yobiko are even more expensive. Some yobiko publish modified commercial versions of the proprietary texts they use in their classrooms through publishing affiliates or by other means, and these are popular among the general population preparing for college entrance exams. Yobiko also administer practice examinations throughout the year, which they open to all students for a fee.

In the late 1980s, the examination and entrance process were the subjects of renewed debate. In 1987 the schedule of the Joint First Stage Achievement Test was changed, and the content of the examination itself was revised for 1990. The schedule changes for the first time provided some flexibility for students wishing to apply to more than one national university. The new Joint First Stage Achievement Test was prepared and administered by the National Center for University Entrance Examinations and was designed to accomplish better assessment of academic achievement. -- may remove

The Ministry of Education hoped many private schools would adopt or adapt the new national test to their own admissions requirements and thereby reduce or eliminate the university tests. But, by the time the new test was administered in 1990, few schools had displayed any inclination to do so. The ministry urged universities to increase the number of students admitted through alternate selection methods, including admission of students returning to Japan from long overseas stays, admission by recommendation, and admission of students who had graduated from upper-secondary schools more than a few years before. Although a number of schools had programs in place or reserved spaces for returning students, only 5% of university students were admitted under these alternate arrangements in the late 1980s. -- may remove

Other college entrance issues include proper guidance for college placement at the upper-secondary level and better dissemination of information about university programs. The ministry provides information through the National Center for University Entrance Examination's on-line information access system and encourages universities, faculties, and departments to prepare brochures and video presentations about their programs.

Types of Universities

As of 2011, more than 2.8 million students were enrolled in 780 universities. At the top of the higher education structure, these institutions provide four-year training leading to a bachelor's degree, and some offer six-year programs leading to a professional degree. There are two types of public four-year colleges: the eighty-six national universities and the nifty-five local public universities, founded by prefectures and municipalities. The 599 remaining four-year colleges in 2012 were private (including the Open University of Japan). (e-Stat, 2012).

As of 2011, women accounted for about 41% of all university undergraduates. (e-Stat, 2012). A growing percentage of students are progressing to universities from high schools: as of 2010, 57.8% out of all 18 year old advanced to schools in higher education (universities and colleges), among which 59.2% are males and 56.3% are females (MEXT, 2012 (PDF)). Therefore, higher education is no longer reserved only for men as it has been in the past.

The average annual school and living expenses (tuition fees and living costs) for a year of higher education in 2006 were about 1.9 million yen (US$19,000) for undergraduates (JASSO, 2008) (see statistics). To help defray expenses, students frequently work part-time or borrow money through the government-supported Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO). Assistance also is offered by local governments, nonprofit corporations, and other institutions.

The overwhelming majority of college students attend full-time day programmes. In 1990 the most popular courses, enrolling almost 40% of all undergraduate students, were in the social sciences, including business, law, and accounting. Other popular subjects were engineering (19%), the humanities (15%), and education (7%). ??? - information about HE is also quite old and misleading.

Women's choices of majors and programs of study still tend to follow traditional patterns, with more than two-thirds of all women enroll in education, social sciences, or humanities courses. Only 15% studied scientific and technical subjects, and women represented less than 3% of students in engineering, the most popular subject for men in 1991. ???

The quality of universities and higher education in Japan is internationally recognized. The two top-ranking universities in Japan are often said to be the University of Tokyo and Kyoto University. There are only 5 Japanese universities in the top 200 Times Higher Education Rankings (2011); QS World University Rankings (2011) with the University of Tokyo 25th and Kyoto University 32nd.

For a full list, see the list of universities in Japan at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_universities_in_Japan

Postgraduate Education

Graduate schools became a part of the formal higher education system only after World War II.

As of 2012, among the 780 universities that offer undergraduate programmes, 617 offer graduate programs (582 offer only master's and 428 offer doctoral). 456 out of the 617 universities are private and the rest 161 are public schools (e-Stat, 2012). The parity between public and private graduate enrollments are 44% (174,456 including 16,593 public) versus 56% (98,110) (e-Stat, 2012).

As of 2012, 272,566 are enrolled in graduate programmes, among which 70% are males and 30% are females.

The average annual school and living expenses for a year in 2006 were about 1.75 million yen (US$17,500) for masters' and 2.08 million yen (US$20,800) for doctoral (JASSO, 2008).

Graduate education is largely a male preserve, and women, particularly at the master's level, are most heavily represented in the humanities, social sciences, and education. Men are frequently found in engineering programs where, at the master's level, women comprise only 2% of the students. At the doctoral level, the two highest levels of female enrollment are found in medical programmes and the humanities, where in both fields 30% of doctoral students are women. Women account for about 13% of all doctoral enrollments. ???

Even though 60% of all universities have graduate schools, only 7% of university graduates advance to master's programs, and total graduate school enrollment is about 4% of the entire university student population. ???

The pattern of graduate enrollment is almost the opposite of that of undergraduates: the majority (63%) of all graduate students are enrolled in the national universities, and it appears that the disparity between public and private graduate enrollments is widening. ???

The generally small numbers of graduate students and the graduate enrollment profile results from a number of factors, especially the traditional employment pattern of industry. The private sector frequently prefer to hire and train new university graduates, allowing them to develop their research skills within the corporate structure. Thus, the demand for students with advanced degrees is low. ???

Two year colleges

Junior Colleges

Junior colleges - mainly private institutions - are a legacy of the occupation period; many had been prewar institutions upgraded to college status at that time. More than 90% of the students in junior colleges are women, and higher education for women is still largely perceived as preparation for marriage or for a short-term career before marriage. Junior colleges provide many women with social credentials as well as education and some career opportunities. These colleges frequently emphasize home economics, nursing, teaching, the humanities, and social sciences in their curricula.

Don't understand what's written for polytechnics and junior colleges here.

Special Training Schools

Advanced courses in special training schools require uppersecondary-school completion. These schools offer training in specific skills, such as computer science and vocational training, and they enroll a large number of men. Some students attend these schools in addition to attending a university; others go to qualify for technical licenses or professional certification. The prestige of special training schools is lower than that of universities, but graduates, particularly in technical areas, are readily absorbed by the job market.

Miscellaneous Schools

In 1991 there were about 3,400 predominantly private "miscellaneous schools," whose attendance did not require uppersecondary school graduation. Miscellaneous schools offer a variety of courses in such programs as medical treatment, education, social welfare, and hygiene, diversifying practical postsecondary training and responding to social and economic demands for certain skills.

Technical colleges in Japan

Most colleges of technology are national institutions established to train highly skilled technicians in five-year programs in a number of fields, including the merchant marine.

Sixty-two technical colleges have been operating since the early 1960s. About 10% of college graduates transfer to universities as third-year students, and some universities, notably the University of Tokyo and the Tokyo Institute of Technology, earmarked entrance places for these transfer students in the 1980s.

These colleges are unique in that they accept students after three years of secondary school (grade 9 in the North American system or year 10 in the British system). The five year programme includes a general education programme at the beginning and then becomes increasingly specialized.

A recent white paper (need reference) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology indicated that the colleges of technology are leaders in the use of internships, with more than 90% of institutions offering this opportunity compared to 46% of universities and 24% of junior colleges.

For more details see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colleges_of_Technology_(Japan)

Education reform

Schools

In November 2004, MEXT announced a new reform plan titled “Japan! Rise again!” Among the major proposals included in this plan were the development of a new national assessment system; improving teacher quality through the establishment of professional graduate schools and a teacher qualification renewal system; board of education and school reform; and an overhaul of the funding system for compulsory education, so that local governments will be able to enact necessary educational initiatives without major budgetary concerns.

Since this plan was announced, MEXT has introduced one of its planned initiatives almost every year. In 2007, Japan piloted a National Assessment of Academic Ability in mathematics and Japanese for students in grades 6 and 9. In 2008 and 2009, MEXT published a revised version of the national curriculum for primary through upper secondary school, including special education. This new curriculum places increased emphasis on Japanese, social studies, mathematics, science and foreign languages, with the hope that students will develop “thinking capacity, decisiveness and expressiveness” alongside content knowledge. The challenge to maintain traditional high academic performance while enhancing expression, creativity and joyful learning is one which in the last decade seem to have affected the Japanese education system, with several reforms undertaken in the field. An interesting discussion is offered on the point at http://asiasociety.org/education/learning-world/japan-recent-trends-education-reform.

In 2009, MEXT implemented a new system requiring educators to renew education personnel certificates every ten years, contingent on up-to-date professional development and skills. This complemented a 2008 initiative that required prefectural boards of education to provide extra training to struggling teachers. Currently, MEXT is working on revising standards in university teacher training programs, promoting career education and enhancing counseling in schools, and using school evaluations to target areas for improvement in school management.

Post-secondary

Higher education reform

National University Corporation

Restructuring of national universities in 2009

Administration and finance

Schools

Administration

In Japan, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) sets policy and curriculum, establishes national standards, sets teacher and administrator pay scales and creates supervisory organizations. MEXT also allocates funding to prefectural and municipal authorities for schools. Local governments are responsible for the supervision of schools, special programs, school budgets and hiring personnel.

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), in conjunction with university professors and the Central Council for Education, establishes broad guidelines for the content of each school subject from pre-school education through senior high school. The central government determines fundamental standards for schools to formulate their education curricula. In accordance with this, each school has been organizing and implementing its own distinctive curricula, taking into consideration the condition of the local community and school itself, the stages of mental and physical growth and the characters of children, pupils or students. Ministry specialists prepare teacher guidebooks in each subject with input from experienced teachers. All schools use the same texts, though how a text is taught is teacher-dependent.

At the prefectural level, there is a board of education comprised of five governor-appointed members; this board is responsible for several activities, including appointing teachers to primary and lower secondary schools, funding municipalities, appointing the superintendent of education at the prefectural level, and operating upper secondary schools.

Within the municipalities, there are boards of education appointed by the mayor. These boards are responsible for making recommendations on teacher appointments to the prefectural board of education, choosing textbooks from the MEXT-approved list, conducting in-service teacher and staff professional development, and overseeing the day-to-day operations of primary and lower secondary schools. In the schools, principals are the school leaders, and determine the school schedule, manage the teachers, and take on other management roles as needed. Teachers are responsible for determining how to teach the curriculum and for creating lesson plans, as well as being in contact with parents.

Finance

Public schools are funded by a combination of support from the national, municipal and prefectural governments. Public upper secondary school did require tuition, but in March 2010, the government passed a measure intended to abolish these fees. Now, schools receive enrollment support funds that they apply to the cost of their students’ tuition which equals about $100 a month, per student. However, if these funds are not sufficient, the students must make up the difference. If students come from a low-income household, the government provides further subsidies of up to $200 a month.

Private schools also receive a great deal of public funding, with the Japanese government paying 50% of private school teachers’ salaries. Other forms of funding are capital grants, which go to private schools for specific costs, including new buildings and equipment. While private schools are considered to be more competitive and prestigious than public schools, public schools still account for 99% of primary schools and 94% of lower secondary schools. There are many more private upper secondary schools, however; 23% of upper secondary schools are classified as private.

In 2008, Japan spent 4.9% of its GDP on education – lower than the OECD average of 5.9%. However, Japan spends $9,673 per student, higher than the OECD average of $8,831.

Post-secondary

Significantly over 90% of Junior colleges and professional training colleges in Japan are private institutions (as much as a large proportion of universities). The large presence of private sectors in tertiary education partially explains also the very low level of government funding and strong private financial support. An remarkable exception is that of Kosen: 87.3% of institutions and 87.5% of students there are publicly funded, national institutions organized through the Institutes of National Colleges of Technology

Quality assurance, inspection and accreditation

Schools

Schools are evaluated and inspected by municipal and prefectural board of education supervisors, who are expected to provide external guidance on school management, curriculum and teaching. Typically, these board of education supervisors are former teachers and administrators.

As of 2009, teachers are also required to renew their education personnel certificates every 10 years, after undergoing professional development to ensure that their skills and knowledge are up to date. This new system ensures ongoing professional development, and also provides schools with the ability to remove teachers who are not willing to upgrade or renew their certifications.

A final accountability measure is the newly introduced National Assessment of Academic Ability, a set of examinations in Japanese and mathematics for students in grades six and nine that began in 2007. The results of these examinations are used by schools and prefectures to plan and make policy decisions.

Post-secondary

Information society

Towards the information society

Information society strategy

E-learning and ICT implementation in education

The most recent as well as comprehensive research report (PDF) regarding the e-learning and ICT implementation in Japanese higher education is provided by CODE commissioned by MEXT made 2010-2011, covering the total number of 1,202 responded institutions in higher education, including universities, junior colleges, and technical colleges.

What is remarkable is that the average of 35.7% higher institutions (national:35.8%; public 35.3%, private: 32.2%) answered that they exercised some sort of internet-based distance learning (p.134).

Besides, the average of 16.0% (433 divisions) answered that they provide full-online course delivery (national: 20.8%, public: 17.6%, private: 14.2%) (p.133).

Distance learning

Distance learning in secondary education

Distance learning in higher education

As of 2012, with the approval of the Distance Education Universities Law (e-Gov), 27 undergraduate, 10 graduate, and 17 undergraduate-graduate institutions and 11 distance education junior colleges are authorized to provide distance learning programs. Distance education higher institutions are run privately (100%) and most are dual-mode (89%), although this could change over time. (e-Stat, 2012).

Currently seven universities are single mode and focus exclusively on distance education. Three of these offer only undergraduate programs, one offers only graduate programs, two offer both undergraduate and graduate programs, and one is a junior college; all of these universities show a high e-learning orientation , presumably a natural consequence of not having campus-based students (Miyazoe & Anderson, 2012).

The number of undergraduates is 217,236 (or 7.8 % out of the total undergraduate students), and the number of graduate students is 8,241 (or 2.9%) (e-Stat, 2012).

Open University of Japan

The Open University of Japan, formerly the University of the Air (Hoso Daigaku), is the largest distance learning institution of higher education, with about 85,000 enrollments (among which about 80,000 are undergraduates and 5,000 are graduates) in 2012.

A particularity of distance learning program of OUJ lies in its providing courses in both face-to-face and distance modes. Many of the courses are offered as video lectures (TV and Internet) as well as face-to-face class meetings (weekly or intensively). Though it is the most obvious candidate to develop e-learning, it is slow in responding to the new environment.

In conjunction with the re-structuring of NIME and its graduate programs (Sogo Kenkyu Daigakuin), now merged into OUJ, master's level graduate programs were re-organized in 2009. New courses of e-learning and information management were further open in 2012 April.

CODE

The National Institute of Multimedia Education (NIME) started off life as an inter-university research institute and had many similarities to national iniatitives such as SURF and Norway Opening Universities.

In April 2004, NIME ceased to be an inter-university research institute and became an independent administrative institution. While this organizational change was not without a degree of confusion, NIME was evaluated for the first time in 2005, earning considerable praise for the way it had managed to continue with its original work and at the same time launch some new activities.

NIME ended in 2009 and its work was transferred to Center of ICT and Distance Education (CODE), a research center of the Open University of Japan.

New attempts of traditional universities

Past attempts by Japanese universities to offer Internet-based classes have been of an experimental nature, with the main objective being limited to the advertisement of the universities concerned. Since the change in the regulations in 2001, there have been more serious attempts to set up e-learning courses including at some top-ranking universities. Two such examples among the national universities are Tohoku University in the Miyagi prefecture and Shinshu University in Nagano. Tohoku University’s plan is a very bold and comprehensive one, while Shinshu University’s programme is far more grounded and has already made some concrete progress.

Two top private universities, namely Keio University and Waseda University, both have solid track records in experimentation with e-learning and are also each actively planning to open an Internet school in the near future. Keio has a distance education course; Waseda has night schools that already offer about 30 on-demand video streaming lectures on the Internet. Among the CEO judged awards, Keio won four awards, Waseda five, and Ritsumeikan three.

Kumamoto University

Tohoku University

The university was the first to start comprehensive and virtual graduate programmes in Japan, in an ambitious programme called the Internet School of Tohoku University (ISTU). The programme envisages a full-fledged graduate school covering political science, literature, economics, law, engineering, international relations, medicine, pharmacology, dentistry, and education. It plans to set up satellite campuses in Japan and also to seek affiliation with universities overseas. The initial offerings will be limited to the engineering divisions. An intermediate goal is to have 40% of all courses on campus on the Internet by the year 2007. In 2002, the university concurrently set up a new department called Education Informatics that will support the operation of the ISTU.

Shinshu University

Starting in April 2002, the university opened an e-learning graduate course on information technology leading to a doctoral degree. (See http://cai.cs.shinshu-u.ac.jp/sugsi/Nyushi/sugsi/sugsi-press.html.) There were more than 1000 inquiries after the announcement and now there are 81 students enrolled – with 80% of them holding full time jobs. The digital content is open to the public and fully accessible, including the interactive programmes. They accepted the first batch of students while the contents were not ready, but the production is in progress at a fairly good pace. (See http://server1.int-univ.com/CaiSupport/)

Waseda University

Waseda has been experimenting with an international collaboration in the use of a video conferencing system, called Cross Cultural Distance Learning (CCDL), which has a membership of 21 universities from 21 countries, including the Universities of Edinburgh and Essex. (See https://ccdlsrv.project.mnc.waseda.ac.jp/ccdl/index.asp.) CCDL is a part of a broader Waseda programme, called Digital Campus Consortium. It has also set up a subsidiary company called Waseda Learning Square to provide life-long learning courses. While its overall reputation trailed behind Keio for some time in the late 1980s and early 1990s, today it has re-established its brand with a wide range of initiatives from new professional graduate schools to new campus plans.

Keio University

Keio is advanced in its use of the Internet and its applications. In 1990, it opened its Shonan Fujisawa Campus (SFC), which received wide and positive publicity for its innovative undergraduate and graduate education; this fosters individual creativity while establishing IT as an integral element of education. Celebrated as one of the most significant higher education innovations, the SFC attracted top-calibre students and established its name not only in the IT world but also in other policy fields. Prior to SFC, Keio had established the WIDE Project in 1988, with a consortium of over 100 universities and corporations, which in turn spun off the first Internet provider in Japan, Internet Initiative (IIJ). WIDE is now responsible for the operation of a DNS server and is also experimenting with IPv6. Another programme under WIDE is the School of the Internet (SOI), which is experimenting in e-learning with six participating universities, including the University of Tokyo and Chiba Commerce University. The programme records live lectures that are later put on the Internet; an interesting feature is that students’ work is left on the Internet for mutual evaluation.

Innovative Universities

Sanno University

Sanno (The University of Industrial Productivity) launched several courses in business-related skills such as accounting, though their delivery is limited to fairly conventional access to video with limited interactivity.

Ritsumeikan University

Ritsumeikan is another well-respected private university that has established its repu-tation on the basis of its innovative reform measures in the 90s. It is well known, but had always been considered as the least desirable of the six best private schools in the Kansai area (of Western Japan close to Osaka). Under the strong leadership of its chairman, who used to be a non-faculty administrator within the university, it opened its Kusatsu Campus, which is now well-known for its forward thinking in educational content; it has been launching all initiatives from IT education, outsourcing in order to develop creative linkages with local industry. While Ritsumeikan has no specific plan for e-learning, it has the management style and ability to move quickly, unlike many other universities. ???-- am not sure if it's right to list here ???

Other institutions

For more details see the report The e-University and Potential Markets in Japan at http://www.matic-media.co.uk/ukeu/UKEU-r05-japan-2005.doc for information.

JOCW

National initiatives - MEXT

(sourced from http://www.nime.ac.jp/reports/004/pdf/report2006.pdf)

In recent years, changes in the environment surrounding higher education and the progress of ICT

have led to an increasing need for education that is effective, efficient, and based on the demands for the greater sophistication and diversification of educational content. Education using ICT and elearning are increasingly being introduced as methods to meet these needs, and their promotion is seen as an important issue in government policy.

The New IT Reform Strategy by the Government (January 2006) and the Priority Policy Program 2006 (July 2006), formulated by the government’s Strategic Headquarters for the Advanced Information and Telecommunications Network Society (IT Strategic Headquarters), state that the government will:

- aim to increase by more than double the ratio of undergraduate faculties and graduate schools which implement e-learning education or distance learning using the Internet, improve cooperation between domestic/international universities and companies as well as promote the further education of members of society through the promotion of e-learning education programs using the Internet at universities, etc.

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) has been conducting its Support Program for Contemporary Educational Needs, since 2004. Under this program, the theme of the development of e-learning programs for fostering human resources in line with needs was suggested, and education using ICT and e-learning are being promoted. By this promotion theme of the Ministry, 13 universities or colleges of technology were selected for financially support to develop e-learning courses in 2006. Responding to this state of affairs, our research, which was conducted in collaboration with MEXT, offers an analysis of the current state of education using ICT at Japan’s higher education institutions and the inherent issues, and also aims to provide some basic data and information to address policy issues surrounding higher education and IT strategy

Lessons learnt

References

Report on education using ICT including e-Learning, 2006 (for tertiary education in Japan)

MEXT (2004), The development of Education in Japan

OECD Review of Tertiary Education, Japan 2009

top 200 Times Higher Education Rankings (2011)

QS World University Rankings (2011)

comprehensive research report (PDF) regarding the e-learning and ICT implementation in Japanese higher education, provided by CODE

enrollment numbers and figures of the Open University of Japan

Center of ICT and Distance Education (CODE)

For OER policies and projects in Japan see Japan/OER