Welcome to the Virtual Education Wiki ~ Open Education Wiki

Belgium

| Belgium | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Kingdom of Belgium |

| Capital city | Brussels - Belgium/OER says Brussels |

| Population | 11584008 - Belgium/OER says 11,000,000 |

| Country code (ISO 3166) | be |

| National language(s) | German, Dutch, French |

| Regional languages | |

| Is included in | OECD, Europe, European Union, United Nations, Benelux, NATO |

You can go directly to the Virtual Campuses in Belgium wiki page.

by Nikki Cortoos and Tom Levec and others

For entities in Belgium see Category:Belgium

For a description of OER in Belgium see Belgium/OER

Partners and Experts in Belgium

- AVNet - K.U.Leuven

- EuroPACE

- Audiovisual Technologies, Informatics and Telecommunications bvba (ATiT)

Note: One of the universities in Belgium is K.U.Leuven.

Belgium in a nutshell

The Kingdom of Belgium is a country in northwest Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts its headquarters, as well as those of other major international organizations, including NATO. Belgium covers an area of 30,528 km2 (11,787 square miles) and has a population of about 10.5 million. Belgium is a federal state in Europe with a constitutional monarchy, founded in 1830, and its capital is Brussels.

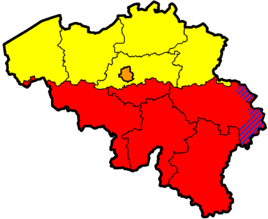

The citizens of Belgium are called Belgians. Straddling the cultural boundary between Germanic and Latin Europe, Belgium is home for two main linguistic groups, the Dutch speakers/Flemings and the French speakers, mostly Walloons, plus a small group of German speakers. Belgium's two largest regions are the Dutch-speaking region of Flanders in the north, with 59% of the population, and the French-speaking southern region of Wallonia with 31% of the population. The Brussels-Capital Region, officially bilingual, is a mostly French-speaking enclave within the Flemish Region and near the Walloon Region, and has 10% of the population. A small German-speaking Community exists in eastern Wallonia. Belgium's linguistic diversity and related political and cultural conflicts are reflected in the political history and a complex system of government.

History

The name 'Belgium' is derived from Gallia Belgica, a Roman province in the northernmost part of Gaul that was inhabited by the Belgae, a mix of Celtic and Germanic peoples. Historically, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg were known as the Low Countries, a somewhat larger area than the current Benelux group of states. From the end of the Middle Ages until the 17th century, it was a prosperous centre of commerce and culture. From the 16th century until the Belgian revolution in 1830, many battles between European powers were fought in the area of Belgium, causing it to be dubbed "the battlefield of Europe" and "the cockpit of Europe" - a reputation strengthened by both World Wars. Upon its independence, Belgium eagerly participated in the Industrial Revolution. Its King privately possessed the "Congo Free State" in Southern Africa until it was later annexed by the Kingdom of Belgium as the Belgian Congo" until it became independent as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The second half of the 20th century was marked by the rise of communal conflicts between the Flemings and the Francophones fuelled by cultural differences on the one hand and an asymmetrical economic evolution of Flanders and Wallonia on the other hand. These still-active conflicts have caused far-reaching reforms of the unitary Belgian state into a federal state. There is constant speculation by observers that this process of devolution might lead to the partition of the country.

Source Wikipedia's page on Belgium

Regions and Communities

Belgium is a double federation of:

- 3 Communities which are responsible for the person-related issues such as education, welfare, public health and culture:

- the Dutch-speaking Community / Vlaamse Gemeenschap: Government, Ministry and Parliamant

- the French-speaking Community / Communauté Française: Government, Ministry and Parliamant

- the German-speaking Community / Deutschsprachige Gemeinschaft: Ministry and Parliament

- 3 Regions which are responsible for the territorial issues such as economy, infrastructure, agriculture, environment and employment

- the Flemish Region

- the Walloon Region

- the Brussels-Capital Region (officially bilingual)

- There are four language areas:

- the Dutch area: the provinces* in Flanders: Antwerp, Limburg, Flemish Brabant, West Flanders, East Flanders

- the French area: the provinces* in Wallonia: Hainaut, Walloon Brabant, Namur, Luxembourg, Liège

- the bilingual area in Brussels-Capital with 19 municipalities

- the German area: the 9 municipalities of the “East Cantons” / Eupen-Malmedy

* The most important or most frequent optional responsibilities of the provinces are education (the provinces organise educational institutions, secondary or higher), culture, social welfare, heritage sites and assets, etc.

Source: The Education System in the Flemish Community of Belgium (PDF - EN - 5 pages), 2006/07

Education in Belgium

Article 24 of the Belgian Constitution (p. 11/60 - EN - PDF lays down the principle of the freedom of education and provides for the existence of state-organised teaching. Within this constitutional framework, two networks of institutions of higher education have developed extensively:

- Public institutions set up by the state and administered by the (linguistic) communities, or by the provincial or municipal authorities.

- Private institutions of which the majority is denominational (such as Roman Catholic) and which receive financial aid from the state, subject to certain conditions. The minority is not affiliated to a particular religion: the Freinet schools, Montessori schools or Steiner schools, which adopt particular educational methods and are also known as ‘method schools’.

For details about education in belgium, visit http://www.expatarrivals.com/belgium/education-and-schools-in-belgium

Such as referenced in Article 24, "Access to education is free until the end of compulsory education". In Belgium, both primary and secondary education is obligatory.

| Level | Age | Year | Compulsory | stages and cycles* | Additional information |

| 2 | |||||

| Kindergarten/Nursery/pre-primary / maternel (FR) or kleuteronderwijs (NL) | 3 | 1 | stage 1, 1st cycle | children that are 2 years and 6 months on 30 September can enter Kindergarten | |

| 4 | 2 | ||||

| 5 | 3 | ||||

| Primary education / primaire (FR) or basisschool/lagere school (NL) | 6 | 1 | c | stage 1, 2nd cycle | Note: in the French Community, the schools where Kindergarten and primary education are combined are called les écoles fondamentale |

| 7 | 2 | c | |||

| 8 | 3 | c | stage 2, 3nd cycle | ||

| 9 | 4 | c | |||

| 10 | 5 | c | stage 2, 4nd cycle | ||

| 11 | 6 | c | |||

| Secondary education / secondaire (FR) or secundair/middelbaar (NL) | 12 | 1 | c | stage 3, 5th cycle |

|

| 13 | 2 | c | |||

| 14 | 3 | c | |||

| 15 | 4 | c | |||

| 16 | 5 | c | |||

| 17 | 6 | c | |||

| Higher Education / supérieur (FR) or hoger (NL) | 18 | 1 | cycle1: Bachelor (3 yrs) |

| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 2 | ||||

| 21 | 3 | ||||

| 22 | 4 | cycle 2: master (1-2yrs) | |||

| 23 | 5 |

Pre-primary Education

- Dutch Speaking Community: kleuteronderwijs

- French Speaking Community: enseignement maternelle

- German Speaking Community: Kindergarten

Free pre-primary school facilities are provided for children who have reached age two and a half. Where places are limited, priority is given to mothers working full-time. These pre-schools are often attached to a primary school. Attendance is not compulsory but it is very popular (it is clearly cheaper than other childcare alternatives, for example) and more than 90 percent of children in this age bracket attend. By age five 99 percent of children are in school.

There are few formal lessons. As children get older there are supervised tasks and specialised lessons in subjects such as music, a second language and gym, and everything is done with an emphasis on play.

Special needs education is also provided on this level.

Primary Education or in the:

- Dutch Speaking Community: lager onderwijs

- French Speaking Community: enseignement primaire

- German Speaking Community: Grundschule

Primary school education begins on the 1st September of the year in which a child reaches the age of six (although some children are admitted at age five if they are considered ready) and is free to all. It lasts for six years and a whole range of academic subjects are studied. There is a strong language emphasis. For example schools in the German community must teach French from the first or second year and in Brussels Dutch schools must teach French and French schools must teach Dutch – commune schools start this during the last year of pre-school.

Primary education consists of 3 cycles:

- First cycle (years 1 and 2)

- Second cycle (years 3 and 4)

- Third cycle (years 5 and 6)

Homework is given from an early age and a high level of parental involvement is encouraged.

Special needs education is also provided on this level. Pupils can then go to special needs primary schools or follow integrated education (geïntegreerd onderwijs (GON)) in which primary schools and special needs primary schools work together. The pupils that, although they have special needs, are able to take part in ordinary primary schools, can follow some or all lessons and activities there, and this either permanently or for a period of time.

Secondary Education or in the:

- Dutch Speaking Community: secundair onderwijs

- French Speaking Community: enseignement secondaire

- German Speaking Community: Sekundäre Erziehung

Secondary education is also free and begins at around age 12. It lasts for six years and consists of three cycles each lasting two years. Parents may be expected to make a contribution towards the cost of text books.

In the first year of secondary education all pupils follow the same programme. From the second year onwards a range of options can be chosen according to preference and ability. These will lead to education of a general nature or with a more technical, artistic or professional slant. Often schools will specialise in one of these streams or will have different sections for different streams. Within the streams pupils continue to choose from further options throughout secondary school resulting in a broad education weighted towards their preferred subjects or career.

Assessment is ongoing throughout secondary education and students receive a diploma at the end of their studies. For those who have followed a general range of subjects the next step is normally higher education.

Technical students often go to university or college to study related subjects or may start working straight after school. Vocational students typically begin working part-time to complement their studies from age 16 and then move into full-time employment.

Those who have followed the artistic options usually go on to higher education, for example to art colleges or specialist music conservatories but may go to university or college, depending on the options they choose. Some art colleges have a secondary section starting from the third year of secondary school and pupils study for the first two years in a general school.

Special needs education is also provided on this level, pupils then follow special needs secondary education (buitengewoon secundair onderwijs (BuSO).

Doubling (repeating a year)

Children are tested at the end of each year of pre-school, primary and secondary school to decide if they are ready for the next year. The testing takes the form of assessment and supervised tests for younger children and exams for older children. If they are not ready to move up, they repeat the year or "double". The system continues in secondary school, although students are also given an alternative to doubling, which is to go to another study or school form (for instance: from ASO to TSO, ...). Because "doubling" is common, there is usually very little stigma attached to it.

A broad view of the educational landscape in the flanders including general education principles, levels of education, support and quality control, education policies and social developments, as well as useful addresses can be found via the following link: http://www.ond.vlaanderen.be/publicaties/eDocs/pdf/107.pdf

More information on legal documents for the French Community can be found on the portal of the circulars, issued by the French Community (FR).

Education Policy in Belgium

The Belgian Constitution stipulates in Article 24 that everyone has the right to education and therefore established compulsory education for children between 6 and 18 years old. Belgium also provides that access to education is free of charge up to the end of secondary education.

Source: the Belgian Constitution (EN - PDF - 60 pages), 2009, - Article 24, p. 11

Primary and secondary education is compulsory for all children that are living on Belgian territory, which includes:

- foreign children must attend school from the 60th day after they are registered in the “aliens’ register” (vreemdelingenregister) or the citizen’s register (bevolkingsregister) of the city or town they live in

- children without a fixed residence (children living on boats or travel trailers, children of fair or circus organisers or artists, gypsies, ...)

--> sourced from http://www.ond.vlaanderen.be/gidsvoorouders/specifiekesituaties/default.htm#migr

To respect their right to education, special care is also taken that long-term ill children can still follow their lessons, from home or from their hospital.

Two groups organise the educational structure: the public sector (the communes, provinces and communities) and the private sector. In the public sector there are 3 educational networks:

- community schools: neutral on religious, philosophical or ideological convictions

- subsidised publicly run schools: organized by communes and provinces

- subsidised privately run schools: denominational schools and schools which are not affiliated to a particular religion: the Freinet schools, Montessori schools or Steiner schools, which adopt particular educational methods and are also known as ‘method schools’.

Education that is organised for and by the government (community education and municipal and provincial education) is known as publicly run education. Recognised education organised on private initiative is called privately run education.

Use of languages in education

As a result of the constitutional reform in Belgium the Dutch-speaking and the French-speaking higher education systems were separated. The Parliaments of the Flemish and French Communities regulate, by federate law, education, with the exception of the setting of the beginning and of the end of compulsory education, minimum standards for the granting of diplomas, the pension scheme (according to Article 127, p. 37). And they regulate by federate law, the use of languages for education in the establishments created, subsidised or recognised by the public authorities (according to Article 129, p. 38). This is the same for the Parliament of the German-speaking Community (according to Article 130, p. 38). The language of education is mostly conformant to the language area.

Sources:

- the Belgian Constitution (EN - PDF - 60 pages), 2009: Article 127, p. 37 and Article 129 and Article 130, p. 38

- The law of 30 July 1963 (PDF) concerning use of language in education

Objectives of Education

The primary and secondary education missions were stipulated in the Decree of 24 July 2997 (FR).

The Higher Education Acts in Belgium states that the three main tasks of higher education are: cooperation with society; education and research.

Source “The organisation of the academic year in higher education - 2008/09”. Chapter 2: Structures of Higher Education Governance ([1] – EN)

Education policy in Flanders

As a result of the constitutional reform in Belgium the Dutch speaking and the French-speaking higher education systems were separated. The Flemish government wanted to do things ‘differently and better’. This led to a new higher education legislation in the early 1990s and to a policy based on the principles of deregulation, autonomy and accountability.

The Flemish government wanted to treat all institutions on an equal basis. In general, there are two types of institutions: universities and university colleges or "hogescholen". New legislation made the former state universities autonomous and gave them almost the same responsibility as the ‘free’ universities. In terms of deregulation, autonomy and accountability the same principles were introduced for the hogescholen. This led in conjunction with the merger operation in 1995 to a fundamental change in the relationship between the government and the hogescholen. Former centralised and detailed regulations were replaced by a management regime aimed at achieving a balanced combination of broad autonomy and responsibility for the hogescholen. The higher education regulations as a whole – universities and hogescholen – became more integrated. The previous government wanted to bring the decree on universities (1991) and the decree on the hogescholen (1994) into line with each other without affecting the nature of the university and college education. This integration process has been stimulated even more by the 2003 legislation on the restructuring of higher education in order to implement the Bologna Process.

In terms of policy preparation the following organisations play an important role in Flanders:

- The Flemish Education Council (Vlaamse Onderwijsraad - VLOR), founded in 1991, is the advisory and consultative body for all educational matters. All draft decrees in the field of education must be submitted to the VLOR. Furthermore, the VLOR can give advice to the Flemish government on its own initiative. The VLOR consists of separate councils for primary, secondary, higher and adult education and a general council, which is composed of representatives of the organising bodies, school staff, parents and socio-economic organisations, university experts and Education Department representatives.

- The Flemish Socio-Economic Council (Sociaal-Economische Raad van Vlaanderen - SERV), composed of representatives of employers and employees, gives advice on all draft decrees, including those in the field of education. The SERV plays an important role in the relationship between education and the world of work.

- The Flemish Interuniversity Council (Vlaamse Interuniversitaire Raad - VLIR) is an autonomous body of public utility with its own corporate status. It acts as a defender of the universities and as an advisor to the Flemish government on university issues (consultation, advice and recommendations).

- Similar for the institutions of non-university HE there is the Flemish Council for hogescholen ([VLHORA), founded during the academic year 1996-1997, represents the hogescholen and gives advice and makes proposals to the Flemish government with regard to the education in the hogescholen. At the same time it can provide consultation among the hogescholen.

- The National Union of Students in Flanders (VVS), the umbrella organisation of student unions at Flemish universities and hogescholen, gives advice at the request of the Flemish government.

Education policy in Wallonia

- The HEIs in the Flemish Community of Belgium are free to draft long-term strategic or development plans and they are free to take the governmental priorities into account or not, as they decide.

- The decree defining higher education in the French Community of Belgium provides the higher education objectives and the mission of the institutions.

- In the German-speaking Community of Belgium, the mission and strategic priorities of the Autonome Hochschule were not established by the institution, but by official decree in 2005.

Source “The organisation of the academic year in higher education - 2008/09”. Chapter 2: Structures of Higher Education Governance ([2] – EN)

In terms of policy preparation the following organisations play an important role in Wallonia:

- The Federation of the French-speaking Students in Belgium / Fédération Des Etudiants Francophones (FEF) represents local student unions. It engages in debates and defends ideas around the central concept of the democratization of HE. This concept includes free access, participation of students in the decisions regarding them, adequate public financing, a reflection about pedagogy and the quality of teaching in HE. Source European Students’ Union (ESU) web site (EN)

- The Council of Rectors of the French-speaking universities of Belgium / Conseil des Recteurs des universités de la Communauté française de Belgique (CREF)

- The Council of the Organising Powers of Official Public Funded Education / Conseil des Pouvoirs organisateurs de l'Enseignement Officiel Neutre Subventionné (regional and local level)] (FR)

- The Federation of the Independent subsidized “Free” Schools / La Fédération des Etablissements Libres Subventionnés Indépendants (FELSI) (FR), including HEIs

- The Federation of Catholic Higher Education / Fédération de l’enseignement supérieur catholique (FédESuC) (FR)

- The Inter-University Council of the French Community of Belgium / Le Conseil Interuniversitaire de la Communauté française de Belgique (CIUF), created by the Decree of 9 January 2003, is a public agency comprising all nine universities and university faculties of the French Community. CIUF’s main missions are to:

- submit opinions on any matter related to university education;

- organize the dialogue between academic institutions and vis-à-vis students and other institutions of higher education;

- promote inter-university and inter-faculty collaboration;

- ensure the representation of the higher education institutions of the French Community in various national or international institutions.

Schools in Belgium

A list of all schools in in Belgium can be found via http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_schools_in_Belgium

Schools in the Brussels Region

A list of all schools from nursery schools to universities in the region of Brussels can be found via the link below. The educational opportunities in Brussels are unlimited since Brussels is a bilingual city with both Dutch and French as the official languages. All schools in Brussels teach in either one or the other and each one teaches the basics of the other language. A center of international presence in the post-war period, Brussels has a number of international schools, among them the International School of Brussels and the three European Schools for children of parents working in the EU institutions. These provide education along British, American, French, German, Dutch, Scandinavian and even Japanese lines. Brussels is home to several universities and two drama schools. In addition, there is a choice of nine major Business Schools where students receive a quality training and education. For more information and list of all pre-schools, primary schools, secondary schools, universities, colleges, polytechniques, art schools and other vocational institutions, go to: http://www.europe-cities.com/en/588/belgium/brussels/schools/

Nursery Schools in Wallonia

In the French speaking Community, kindergarten or nursery education is for children between the age of 2.5 to 5 years old. This period of education is not compulsory but it helps to develop social skills in the children and also allows the identification of potential difficulties and disabilities in children before they become older and get into primary school.

In Wallonia, the nursery is part of the pedagogical continuity of the three stages of learning objectives included in developing core skills from kindergarten, primary and then finally secondary education.

For a list of nursery schools in the French speaking Community, visit the following site:

http://www.enseignement.be/index.php?page=23836&navi=149

Primary Schools in Wallonia

Both pre-school (nursery) and primary education in Wallonia are seen as very fundamental even though the former is not compulsory. Compulsory primary education is between the ages of 6 and 12 years of age and is based mainly on the teaching of language, reading and mathematics. It culminates with the 'Certificate of Basic Education' (CEB). This certificate gives access to secondary education.

In Wallonia, learning a second language other than French is compulsory from the fifth year. In the Brussels region, learning a second language starts from the third year of primary school.

Some kindergarten and primary schools teach some subjects in another language other than French. This is part of what is known as the 'Language Immersion Programme'. For more information about the immersion programme and a list of schools carrying out the programme, visit the following link:

http://www.enseignement.be/index.php?page=23801&navi=33

A list of all secondary schools is also available via the following link:

http://www.enseignement.be/index.php?page=23836&navi=149

You can also find a list of all school and public holidays observed by all nursery, primary and secondary schools in wallonia on the same link as above.

Secondary Schools in Wallonia

For a list of all schools in Wallonia including all French speaking schools in Wallonia, visit the following links:

- http://www.liensutiles.org/ecolebe.htm

- http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_des_%C3%A9coles_secondaires_en_Belgique

- http://www.wallonie.be/fr/citoyens/apprendre-et-se-former-tout-au-long-de-la-vie/enseignement-secondaire/index.html

- http://www.enseignons.be/actualites/2011/04/06/secondaire-liste-ecoles-completes/

Independent Private Schools in Belgium

Independent private schools in Belgium are mostly international schools serving the expatriate community. However, some Belgian children also attend the schools. Instruction is usually in English. The schools typically draw students from many countries so that children receive a truly global perspective. Some of the private schools in Belgium include the Antwerp International School, Brussels International School, St John's International School, Brussels Junior Academy, Da Vinci International School, British International School. There are a good number of British International schools. A list of independent private schools in Belgium can be obtained via the following links:

- http://www.independentschools.com/belgium/

- http://privateschool.about.com/od/belgiumschools/Belgian_Schools_Online.htm

A list of all international schools in belgium is found via the following link:

British Schools in Belgium

British schools in Belgium are established as independent international schools with each school developing and following its own mission. Most normally follow British National Curriculum and offer a broad based educational program. The provide education integrated with childcare provision, creating a foundation for individual development and a sound basis for life-long learning. Capitalising on small class sizes, allowing a high degree of individual attention, most British schools in belgium success in an atmosphere where pupils and students feel cared for and valued. There are strong French language and music programs in some of the schools, excellent Information Technology facilities, Special Needs provision and a wide range of extracurricular activities.

They normally admit children of all nationalities, cultures and religions affiliations and is ideal for children who just relocated to Belgium. Most British Schools in Belgium are members of the European Council of International Schools and their programs usually include French, Dutch, English, Information Technology, Art, Music, Swimming, amongst others. The fees are usually very expensive ranging from EUR 6,000 to EUR 17,000.

For a list of all British Schools in Belgium from pre-Kindergarten /toddlers - 18 months to 2½ years, kindergarten nursery - 3 to 5 years, reception - 4 to 5 years, primary - 5 to 11 years, secondary middle school and secondary high school, visit the following link: http://www.expatica.ru/education/school/british-schools-1427_8454.html

Special Needs Schools

Children with speical needs and disabilities and/or learning difficulties are catered for within mainstream schools. However, there are separate specialist schools available and in the case of severe disability, children may be taught at home or be exempt from compulsory schooling. Both inclusion and equality is Belgium's approach in dealing with the issue of special needs in education and there is an unwavering commitment to giving every child the right to an education which maximises their potential. For a complete information on and list of special needs schools, visit the following website: http://belgium.angloinfo.com/countries/belgium/specialneeds.asp or visit the Flemish Ministry of Education and Training web page on special needs education

Special Needs School Type 4: education for children with a physical disability (also financed by the government)

- An example of such a state-financed school is the physical rehabilitation centre for children and youth Pulderbos where special needs, secondary education is given to patients staying temporarily at the centre - in collaboration with the patient's own school. Nursery and primary education is also given there, but this is financed by the state as a type 5 school:

Special Needs School Type 5: education for children staying in a hospital or institution (also financed by the government)

- Hospital Schools: I learn at the hospital is an umbrella non-profit organisation consisting of Belgian hospital schools and specialised institutions that provides education to long-term ill, hospitalised children at nursery, primary and secondary education level. This is subsidised by the government as it provides special needs education type 5 (long-term ill children and hospitalised children).

- Video chat session from home to class:

- Bednet, as mentioned below, is a Flemish initiative in which primary and secondary school pupils that have a long-term illness, can still participate in class and connect with their classmates through video-chat sessions.

- Take Off asbl, also mentioned below, enables children in the French-speaking Community who have been sick for a long time to continue their education at home or while in hospital through connecting to the class and teacher via videoconferencing.

- 1:1 education at home

- Temporary Education At Home (Tijdelijk Onderwijs Aan Huis (TOAH) in Dutch) enables temporary primary and secondary education for children that are not hospitalised but absent from school for more than 21 days or on a weekly basis due to illness or an accident. The teacher or a staff member goes to the child’s home to teach for 4 hours “class time”.

- Permanent Education At Home (Permanent onderwijs aan huis (POAH) in Dutch) provides education to children who cannot follow the special needs primary or secondary education on a permanent base and due to their special needs, but can they learn though certain "lesson hours" given at their own home.

- School and Illness (School & Ziekzijn vzw (S&Z) in Dutch), provides 1:1 education at home on a voluntary basis (transport costs are charged)

- Relevant initatives/organisations are: the Platform for Education for Ill Children in Flanders (or Platform van Onderwijs aan Zieke Leerlingen in Vlaanderen (PoZiLiV) in Dutch), the foundation Ivens-Boons Fonds in Mechelen (Flanders), ...

Initiatives for underprivileged people (young as well as old), prisoners, ... or "those left out"

- Auxilia is a volunteer organisation in Flanders and Wallonia that enables 1:1 education for underprivileged people or for people that are being left out by existing literacy courses, primary or for who second-chance education is not within their reach or fit to their specific needs. Students can be young people preparing for an exam for the "central exam commission", special needs students that have specific educational interests, prisoners, ... and volunteer teachers then provide personal and customised lessons (on location if needed but transportation costs are charged). The initiative is also present in Spain and France.

French school in Belgium

The Lycée Français International (French International School of Antwerp) is a private school located in Antwerp, Belgium that follows the French curriculum, has a covenant with the French National Education Ministry and pupils graduating from secondary school receive the French degree « baccalauréat ». Instruction languages vary between (combinations of) French, English and Dutch.

Homeschooling

- in Flanders

- for information on Wallonia, you can read more here

Further and Higher education

In Dutch: hoger onderwijs

In French: enseignement superieure

Higher education in Belgium is organised by the Flemish and French communities via state or private institutions (often linked to religious bodies). German speakers typically enrol in French institutions or pursue their studies in Germany.

There are six universities in Belgium which offer a full range of subjects. In most cases students are free to enrol at any institution as long as they have their qualifying diploma. However, those wishing to continue their studies in medicine, dentistry, arts and engineering sciences may face stricter entrance controls including additional examinations.

The government sets the registration fee for each establishment and reviews it annually. There are three fee levels depending on the student's financial situation and that of their family.

The higher education system in Belgium follows a Bachelor/Master process with a Bachelor's degree obtained after three years and a Master's degree after a further one or two years. Both universities and colleges can award these degrees.

Students from outside Belgium coming to study in one of these establishments will have to prove that they have the appropriate entrance qualifications and that they can financially support themselves during their studies.

In higher education, the academic year begins between mid-September and 1 October, depending on the course.

Universities and Polytechnics in Belgium

- Remark: Polytechnics are called University Colleges or "Hogescholen" in Flanders.

On 4 April 2003 the Flemish government approved the Decree on the restructuring of higher education in Flanders. A new qualification structure was introduced. One-cycle programmes have been converted to the level of bachelor’s degree. Two-cycle programmes in hogescholen are academic education: academic bachelor courses and master courses in association with a university. The system should be regarded as a binary system: professional higher education at the ‘hogescholen’ and academic higher education at the universities and at the hogescholen (associations). The ‘hogescholen’ can award academic degrees in cooperation with a university. Still the universities have the monopoly of awarding doctor’s degrees.One of the consequences is that co-operation between universities and hogescholen is increase considerably with the development of associations. Universities and university colleges cooperate intensively, especially in the field of research, in the Associations. These are formed by one university and at least one university college. As a third kind, the Flemish government has recognised a number of "registered" institutes of higher education, which mostly issue specialised degrees or provide education mainly in a foreign language. The educational provision in Flemish tertiary education is laid down in the Higher education register that contains all the accredited higher education programmes in Flanders. There are 39 recognised Higher Education Institutions. The Universities and Colleges are divided into 5 associations. The registered Institutions are not a member of an Association. A few tertiary education institutes are not regulated by the corresponding laws on tertiary education. The Faculty of Protestant Theology in Brussels and the Evangelical Theological Faculty (in Heverlee award degrees in Protestant Theology. They are recognised as private institutes. Whatever their origin, all institutions mentioned above are officially recognised by the Flemish authorities. The following postgraduate institutions have the same status:

- Institute of Development Policy and Management,

- Institute of Tropical Medicine,

- Vlerick Leuven-Gent Management School

We refer to the overview of all Flemish HEI's to get a complete overview.

In Flanders, the following higher education courses are provided:

- Bachelor courses( Professional bachelor courses and Academic bachelor courses)

- Master courses

- Further training programmes

- Postgraduates and updating and in-service training courses

- Doctoral programmes

Higher professional education exclusively consists of professionally oriented bachelor courses, which are only organised at colleges of higher education. Academic education comprises bachelor and master courses, which are provided by universities. Also colleges of higher education belonging to an association are allowed to provide academic education.

Adult Education In Flanders there are several publicly funded education, training and developmental provision schemes for adults. Within part-time adult education, 3 different actors can be distinguished:

- continuing education (OSP): with more than 250,000 course participants, continuing education is the most important pillar in adult education. Continuing education is provided in centres for adult education which are recognised and funded by the authorities.

- supervised individual study (BIS): BIS has discontinued. It is however published in our research list.

- adult basic education: the 29 centres for basic adult education try to provide a broad and varied range of basic education programmes: languages, mathematics, social orientation, ICT, introduction in French and English and stimulation and student counselling activities.

In contrast with continuing education and BIS, courses in basic education are free of charge.

Lifelong Learning

On 31 March 2003, the Training and Alignment Information Service /Dienst Informatie Vorming en Afstemming (DIVA) was launched. DIVA co-ordinates the educational provision for adults in Flanders. DIVA facilitates the co-operation between the policy fields Education and Training, Employment, Culture and Economy. DIVA’s partners are the educational networks, Flemish Employment and Vocational Training Agency (VDAB), Flemish Institute for the Self-Employed (VIZO) and Support Centre for Socio-cultural Work (Socius). These partners represent respectively adult education (including further higher education, OSP, basic education, BIS and DKO), the training courses set up by VDAB, by Syntra and socio-cultural adult work. An awareness-raising campaign was launched: http://www.wordwatjewil.be (“Become what you want”)

Universities and Polytechnics in Wallonia

In Wallonia distinctions are made between:

- University education at Universities (Universités) & University-Faculties (Facultés Universitaires). Scientific research is an important aspect of university education. The universities, recognised and subsidised by the French Community of Belgium, are grouped together in the form of university academies or associations.

- Non-university education at Colleges (Hautes Ecoles), which are equivalents of the Flemish “Hogescholen”, Institutes of Higher Education, Colleges of Art/Art Academies (Les écoles supérieures des arts) and Higher Institutes of Architecture (Les Instituts Supérieur d'Architecture).

We refer to the overview of all Walloon HEIs to get a complete overview.

A list of all art schools in both the Flanders and Wallonia is available via the following link:

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_des_%C3%A9coles_d'art_en_Belgique

Education reform

Schools

Post-secondary

The language partition in Belgium is still apparent to this day. The language, used in education in Belgium today, depends on the language area the institution is located in, as mentioned in Belgium in a Nutshell / Communities & Regions: you have the obvious division of the 3 language-defined communities and the capital Brussels, which is bilingual. The dominant languages in the HEIs in these separate entities are accordingly.

Higher education reform in Wallonia

Recent mergers in 2007-2008 created the The University-College of the Province of Liege / La Haute Ecole de la Province de Liège (HEPL) from Rennequin Sualem, Léon-Eli Troclet and André Vésale, as well as the new The University-College of Namur / La Haute Ecole de Namur from The Catholic University-College of Namur / Haute école namuroise catholique (HENAC) and University-College of Teaching of Namur / la Haute école d’enseignement supérieur de Namur (IESN). In 2008/2009, 29 University-Colleges became 25: La Haute Ecole libre mosane (HELMo) was the result of the merger of la Haute Ecole mosane d’Enseignement supérieur (HEMES) and la Haute Ecole ISELL. Future mergers are also being planned.

Source http://www.enseignement.be/index.php?page=23811&navi=2537

The Bologna Process in Belgium

The Decree of 31 March 2004 defined the Higher Education for Belgium and promoted its integration into the European area of higher education and universities refinancing.

The Bologna Process has stimulated Flanders in a move towards greater internationalisation. The concept of internationalisation has changed from a focus on the individual to a focus on the ‘system level’, namely the formal structures of higher education. A Flemish credit system based on the ECTS and a Diploma Supplement were already implemented in the early 1990s. More recent changes are:

- implementation of a bachelor and master structure,

- accreditation system in co-operation with the Netherlands,

- more flexible study paths.

The Bologna Process lead to some significant changes in the Belgian educational system, including in the French Community:

- The ECTS (European Credit Transfer System), in which a "credit" is a unit corresponding to the time spent by the student on a learning activity within a programme of studies in a given discipline (a study year is reference point@: 60 credits)..

- Bachelor-master structure or “baccalauréat-maîtrise” structure:

- First cycle - the bachelors with a minimum of three years of study (180 credits)

- Second cycle - the master degree with one to four additional years after obtaining a bachelors degree.

- Third cycle: the doctorate, which only applies to university education and is accessible to students who have completed at least 300 credits.

- Cooperation to ensure the quality of higher education etc.

- Mobility of the students and academic staff

As mentioned earlier, the French Community now distinguishes between universities (offering bachelor, master and doctoral courses) and higher education outside the universities (offering only bachelor courses): colleges (Hautes Ecoles), arts colleges, and institutes of architecture.

Sources

- Information and presentations on The Bologna Declaration at the Enseignement.be web site

- The Wallonia-Brussels Community and the European Higher Education Area”, 1 web page (English) by StudyInBelgium.be.

Relevant Documents

- Re.ViCa wiki page on the Bologna Process

- The Bologna Process - State of the art in the French Community of Belgium (DOC)

- Towards the European Higher Education Area - Bologna Process - National Reports 2004 – 2005 - Belgium -Flemish Community (PDF)

Administration and finance

Schools

Post-secondary

For Belgian and European students, higher education is financed to a very large extent by the public authorities.

Funding in Flanders

The Flemish higher education system is predominantly a public funded system. The Ministry of Education and Training directly funds the HEIs. There is no intermediate independent statutory body.

The public funding system distinguishes three main funding streams:

- the first flow: a core recurrent funding for teaching and research which covers costs of staff, material, equipment, buildings and social facilities of students;

- the second flow: an additional funding for basic research and a funding for basic research allocated by the research council and a funding allocated by the federal state (research networks of universities of both linguistic communities);

- the third flow: public funding for specific research programmes developed by the government, other public organisation, EU, cities and the provinces: such as for justice, social security, energy, sustainability, …. There are also funds for policy oriented research linked to the main policy domains.

Tuition Fees in Belgium

Every year, students must pay a registration fee. University enrolment fees were laid down in a clause in the Law of 27 July 1971 on the financing and supervision of university institutions. Subject to fulfilment of certain educational and financial conditions, students can benefit from student grants or loans. This assistance is supplemented by other benefits such as low-priced meals, assistance granted by welfare services linked to the universities, season tickets for transport, etc.

Source French Community - Structures of education, vocational training and adult education systems in Europe, 2003 Edition – PDF – EN

Tuition fees in Flanders

In Flanders, the tuition fees are low compared to many other countries: - maximum 100 euro for students from the lower socio-economic background (students who are eligible for a grant – about 25% of the student population); - maximum 515 euro for the other students; there is a deduction for students whose parental income is a little bit above the eligible income limit).

The HEIs can raise tuition fees for non-EU students and for advanced master study programme in order to cover the costs of attracting specialists (these programmes are also internationally oriented).

Every student who qualifies for study financing can be supported financially for two bachelors, a master, a preparation programme, a bridging programme and a teacher training programme. As study paths have become more flexible, so too has study financing been made more flexible. A system of study credits has replaced the study year system. The study financing amount is linked to the number of study credits for which the student is enrolled. The new decree extends the possibilities of taking study financing beyond Flanders into the wider Higher Education Space. In the past funding could only be taken across the border if students opted for foreign studies that were not provided in Flanders.

Relevant source on the legal framework is the Decree of 5 August 1995 (FR) established the general organisation of Higher Education in the University-Colleges and was amended by the [3] Decree of 30 June 2006 which modernised the operation and the finances of the University-Colleges.

Tuition Fees in Wallonia

In the French Community of Belgium the amounts of tuition fees are determined by the central education authorities. Donations made to HEIs may be the object of tax relief for donors.

Source “The organisation of the academic year in higher education - 2008/09” Chapter 4: Private Funds Raised By Higher Education Institutions (PDF – EN)

The amount of the registration fee varies depending on the higher education establishment and the type of programme followed. For example, for the academic year 2008-2009, the registration fee for Belgian and EU students is set as follows to register with:

- A university HEI: € 811.00.

- An non-university HEI: from € 165,03 to € 428,56, depending on the duration of the course and if a degree will be obtained during the academic year.

- Non-EU students are required to pay additional annual fees, of which the sum amounts to around € 1,500.00 for the first cycle and € 2,000.00 for the second and third cycles.

Sources

Costs

In the French Community, the unit costs established per student correspond to a normative cost per student, which is established by considering various factors such as, for example, optimal student/staff ratios and other standardised efficiency measures used to calculate what the costs per student ought to be, rather than what they are on an actual or average basis. The French Community of Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany and Malta use an approach based essentially on input in the award of basic funding for research.

While in the German-speaking Community of Belgium, a new funding system for operational costs at the only

HEI (Autonome Hochschule) is being prepared and will be applied from 2009/10. Initiatives in the fields of training and research, taken by this HEI since 2005, can be taken into account for the annual lump sum.

Source “The organisation of the academic year in higher education - 2008/09.” Chapter 3: Direct Public Funding Of Higher Education Institutions (PDF - EN)

Students who enrol in higher non-university education must pay fees (the minerval). The minimum payment is set by regulations (there are special fees for certain foreign students). Subject to certain pedagogical and financial conditions, students can be awarded study grants or loans. The forms of assistance offered also include other benefits, such as low-cost meals, assistance by the social services connected with hautes écoles, season tickets for transport, etc.

Grants

- The Wallonia-Brussels Community grants: grants can be awarded by the French Community of Belgium and by the universities. Web site: Wallonia-Brussels International (WBRI)

- The European Union grants: grants are also awarded within the framework of European programmes :

- The SOCRATES/ERASMUS and LEONARDO programmes

- The ERASMUS MUNDUS programme

- The ALBAN grant programme for students from Latin America. In 2002, the European Commission adopted this programme.

- The Grants of the University Agency of Francophony targeting students, teachers and researchers

Source StudyInBelgium: Financial aspects

Relevant Sources for Wallonia: Financial aspects](FR) on Enseignement.be, with subpages on school fees (FR), social benefits (FR), discount on public transport subscriptions (FR)

Quality assurance, inspection and accreditation

Schools

In Flanders

The system of quality control and promotion by the government is built on 3 pillars:

- The curriculum entity: Final objectives are minimum goals which the government considers necessary and achievable for a particular group of pupils. In concrete terms, this concerns knowledge, insight, attitudes and skills. They are subject-related final objectives but also cross-curricular ones. Final objectives are developed by the Curriculum entity within AKOV. They are submitted to advice by the VLOR, then approved by the Flemish government and finally validated by an Act of the Flemish Parliament. Every governing body or school board must include the final objectives in the school learning programmes.

- The inspectorate: The educational inspectorate of the Flemish Ministry of Education and Training acts as a professional body of external supervision by assessing the implementation of these final objectives.

- Educational guidance: Each educational network has its own educational guidance service (Pedagogische Begeleidingsdienst - PBD), which ensures professional internal support to schools and centres. Schools can call on them for educational and methodological advisory services (innovation projects, self-evaluation projects, support initiatives). Educational guidance works across schools for the in-service training and support of head teachers. Educational guidance also has an important role in the establishment of new curriculums and supports their implementation. If the inspectorate detects shortcomings in schools, the educational guidance service may be called on to address them.

Schools in elementary and secondary education are submitted to a regular external review by the inspectorate. In secondary education, the schedule is drawn up with a focus on school communities (all schools affiliated to one school community are inspected during one particular period). The Parliament Act on Quality Assurance in Education states that every institution has to be inspected at least once every 10 years. To ensure uniformity, all inspection teams use the same set of instruments. Moreover, inspection procedures are identical throughout the Flemish Community. The inspectorate uses the CIPO (Context – Input – Process – Output) model. This model has been used for a while, but is officially obliged by the Parliament Act on Quality Assurance in Education in 2009. The global framework is defined in the Parliament Act, the concrete content in implementation decrees. The interpretation of the different aspects of the model is as follows:

- Context: stable information regarding location, organising body, physical and structural conditions under which the school must operate and on which it hardly has any influence at all.

- Input: information on the conditions under which and the resources with which the school must develop its processes, but which it can influence to a certain extent such as staff (profile, further training and training), financial resources, courses of study offered, pupils (offer, profile)…

- Process: all the pedagogical and school-organisational characteristics which indicate what efforts the school makes to achieve the objectives laid down by the government.

- Output: both the hard output data which show to what extent the objectives (final objectives, curricula, progression/transition...) to be attained are achieved and the softer output data such as the well-being of pupils and teachers.

This choice of model implies that the inspectorate sees the performance of the teachers and principal within the overall school performance and that the school performance is placed within the local context. This model is used from a perspective of accountability and school development. The school inspection is both a means to check data within the school (accountability) and may be an occasion for the school to optimise the quality of the education it provides (development). In addition, the inspection team checks whether the school’s infrastructure is adequate and whether statutory provisions are properly adhered to.

An inspection can result in three types of advice:

- favourable;

- favourable but for a limited time only: in that case a number of shortcomings have been established which must be rectified within a pre-set time frame. Once that period has expired, a progress check will be carried out in relation to said shortcomings;

- unfavourable; this will lead to the rescission of a school’s recognition or part thereof.

Each inspection consists of three phases:

- Pre-analysis of existing sources and on-the-spot

- Actual inspection, consisting of a 3 to 6 days visit at the school. The methods that are used during the inspection visit are interviews, document analyses and observations.

- Inspection report: The conclusions of the inspection team are elaborated in an inspection report. This also contains the final advice. In line with administrative openness, all inspection reports are published on the Internet (www.schooldoorlichtingen.be).

Follow-up procedures were revised in 2006. When a school has been fully inspected a follow-up inspection will take place after three school years. Intermittent follow-ups are only possible if, due to very specific problems, this was so agreed with the inspection team and if it features in the inspection advice. The follow-up will be based on an adjustment plan the school has drawn up.

In Wallonia (French Community)

There is no systematic assessment of educational institutions in the French Community of Belgium. However, there is a multiple oversight system made up of different bodies.

For compulsory education (basic and secondary), an Education Steering Committee (Commission de pilotage du système éducatif) chaired by the General Administrator for Education and Scientific Research has been put in place. It is made up of the general education inspectors, education experts, the representative of the French Community education system, and representatives of the organising authorities, trade union organisations and parent associations. The Steering Committee's many tasks include "providing information, on its own initiative or on request, to the government and Parliament of the French Community, particularly about the state and evolution of the education system, present or foreseeable problems and shortcomings with respect to plans and projections. If the committee has information suggesting that an institution is not implementing or is applying in an obviously unsatisfactory way its recommendations intended to guarantee the quality and equivalence of the education provided in the system's schools, it sends a report to the government, which must take the necessary measures or sanctions."

For tertiary education, an Agency for Assessment of the Quality of Tertiary Education organised or grant-aided by the French Community (Agence pour l'évaluation de la qualité de l'enseignement supérieur organisé ou subventionné par la Communauté française) has the task of ensuring the implementation of the assessment procedures required by law, taking various measures to improve the quality of tertiary education and informing the government, actors and beneficiaries of tertiary education about its quality. The assessment concerns the quality of teaching in the different first- and second-cycle curricula organised by institutions. The curricula to be evaluated and the institutions concerned are determined by the agency based on a 10-year plan, established in such a way that each curriculum is evaluated at least every 10 years. The first 10-year plan covers the period 2008-2018. The assessment is based on a set of indicators that cover all the training and organisation processes to be taken into consideration. It focuses on determining the training objectives sought by the different curricula and the suitability of the means implemented to achieve them. The assessment of the quality of a curriculum in an institution includes the drafting of an internal assessment report, an external assessment carried out by a committee of experts, publication of the results of the assessment (or the refusal to publish) on the agency's site, definition by the academic authorities of a calendar and follow-up plan for the recommendations contained in the final report and their transmission to the agency. The agency then carries out a transversal analysis of the quality of the curriculum in the French Community. In addition, a Higher Education Observatory (Observatoire de l’enseignement supérieur) is responsible for steering tertiary education and developing analysis instruments, scientific reports on the evolution of the student population and indicators on success rates and other aspects.

A General Inspectorate (Service général de l’inspection) made up of specific departments at the different levels and categories of education (ordinary basic, special, social advancement, etc.) is charged with a variety of assessment tasks, including monitoring the level of studies, conformity with the requirements of different decrees, detection of possible segregation measures, and so on. Furthermore, the inspectorate assesses, at the request of the head of the establishment in education organised by the French Community and by the organising authority for grant-aided education, the teaching aptitudes of members of its teaching staff. The members of the General Inspectorate base their assessment and monitoring on facts established through attendance at classes and activities, a review of pupils' work and documents, the results obtained in external assessments that do not lead to qualifications, interviews with pupils, analysis of qualitative data related to failure rates, repeat years or reorientation to other schools and a review of preparations. When the government has decided to carry out an inquiry in one or more schools, the coordinating Inspector General may send one or more staff members of the General Inspectorate to the establishments. Detailed reports are drawn up on the inspections, which may concern a class or one or more schools in whole or in part, and are transmitted to the competent authorities. They may also be detailed in a briefing note transmitted to the relevant service in charge of advising and teaching support. When an organising authority does not take follow-up action on an unfavourable report drawn up by the General Inspectorate, it is obliged to state the reasons for its decision within one month following receipt of the report.

Government commissioners (Commissaires du gouvernement) ensure that decisions taken in higher education institutions are in conformity to legislation.

In compulsory education (l’enseignement obligatoire) each school must have a school work plan that determines all teaching choices and specific actions that the school's teaching staff intends to implement in collaboration with all actors and partners to achieve the organising authority's educational aims. The participation council set up in each school (see section 1.2) is in charge of periodically evaluating implementation of the school's plan, proposing adjustments and submitting an opinion on the school's activity report. For each of the schools it organises, the organising authority must transmit to the Steering Committee by 31 December an annual activity report for the previous school year. The annual activity report includes the assessment of measures taken to achieve the general objectives in the framework of the organising authority's programme, information on success and failure rates, information on appeals against the decisions of class councils and the results of this procedure, and information on the number and reasons for refusals to enrol pupils. Tertiary education establishments are also obliged to draw up and submit an annual report. In colleges of higher education (hautes écoles), the authorities transmit to the Community Education Commission a complete annual report and undergo a quality control inspection every three years on the teaching activities they organise and their other tasks. The curriculum assessment procedure includes two essential phases: an internal self-assessment and an external assessment by a committee of independent experts. Each college of higher education has an education council which can send a reasoned request to the executive board when the majority of its members representing either staff or students consider that the authorities of the college of higher education have failed to implement one or more means foreseen by the plan. A specific procedure is then followed, which in the case of failure may culminate in a reduction of allocations granted to the college of higher education. Each university is also obliged to draw up an annual report containing a description of measures taken for the benefit of students and various statistical data, which is transmitted to the competent minister. In each art college, a staff member is responsible for coordinating quality assessment.

Post-secondary

In Flanders

Assessing the quality of the services that universities provide has become an overriding priority. The Quality Assessment is different in Wallonia and Flanders.

Quality assessment in Flemish higher education is organised at different levels

1. The decretal internal self-evaluation.

2. An external assessment of a particular programme (or cluster of programmes), starting from those self-evaluation reports, carried out by external assessment panels which are coordinated by the Council of Flemish University Colleges, (Vlaamse Hogescholenraad – VLHORA) (www.vlhora.be) and the Flemish Interuniversity Council (Vlaamse Interuniversitaire Raad – VLIR) (www.vlir.be).

Accreditation by the Dutch-Flemish Accreditation Organisation (Nederlands-Vlaamse Accreditatieorganisatie – NVAO), which starts from the assessment carried out by the quality-assurance agency. When positively assessed, programmes are accredited for a period of eight academic years. However, when the NVAO issues a negative decision, institutions may apply for temporary accreditation which is valid for a period of one year and which can be extended twice (research.

In exchange for greater autonomy Flemish universities and hogescholen have implemented a system of internal and external quality assessment. The aim is to improve the quality of study programs. The government has made the institutions themselves responsible for creating the appropriate means for doing this. The so-called “visitations” consist, firstly, of a very important self-assessment (on the basis of a detailed guide) and secondly, the visit and assessment (on the basis of interviews) by an external commission which draws up the final report. As laid down by decree, a visitation for each study program must take place at least once every 8 years. For universities, the first round was completed in 2001; a new round started in 2002 (for non-university tertiary education, a new round started in 2004). Recommendations are, generally speaking, acted upon quite well by the individual institution in question.

At the institutional level, the quality assessment with regard to teaching primarily concerns the evaluation of the individual courses.

The students’ assessment of teaching performance takes the form of a standardised questionnaire, to be filled in anonymously, which provides information regarding, for example, the teaching materials and methods used, the match between the content and the final objectives of the course, the teaching style, etc. Finally, the students may add general comments (such as suggestions, strengths and weaknesses of the course) by means of open questions.

Although the educational authorities in Flanders are greatly in favor of collective research assessments,quality assurance with regard to research is at present mainly the responsibility of the individual universities. The Department of Education has, however, recently commissioned an evaluation of the universities’ research management and quality assurance processes, while the universities themselves were asked to report on their experiences with regard to the research policy management of the authorities.As laid down by decree, a systematic research assessment by each individual university, resulting in a public report, must be carried out at least once every 8 years. From 1999 onwards, most universities have been carrying out bibliometric studies on research output on the basis of publications and its visibility in the natural and (bio)medical sciences. Recently, pilot studies have also been commissioned in some domains of the humanities and social sciences (linguistics, economics, law). Furthermore, self-assessment reports at the level of individual research teams, supplemented by data on commissioned research and output of the teams, are regularly used in internal and external peer reviews. Only one university (Free University of Brussels – VUB) is at present running a systematic research assessment program consisting of complementary bibliometric studies and on site peer review.

In Wallonia

Quality Assessment in the Walloon Higher Education is arranged by The Decree of 8 March 2007, which created a Pedagogical Support and Advice Service for the education organised by the French Community. On 1 September 2007 the decree was enforced, reforming the General Inspectorate Service, which is headed by a General Coordinator under the authority of the Director General of the General Administration of Education and Scientific Research. Some of its Inspection Services are also for Higher Education (Enseignement supérieur) such as the Inspection Service of Social Welfare Education (FR) and the Inspection Service of the Arts Education (FR). On the web site Enseignement.be you can find an overview of the several inspection divisions: The annual administration: inspection (FR). Sources

- http://www.restode.cfwb.be/pgens/sup/superieur.htm?i=mEtsitem_4

- http://www.restode.cfwb.be/pgens/org_cf/insp/inspection.htm

The Agency for the Evaluation of the Quality of Higher Education (l'Agence pour l'Evaluation de la Qualité dans l'Enseignement supérieur) was created by the Decree of 14 November 2002 and is organised or subsidised by the French Community.

Information society

In Belgium, the development of the e-learning knew a notable evolution since the beginning of the years 2000, under the impulse of several public funding, of regional, national or European origin. The large universities of the country have all internal teams in charge of stimulating and adapting existing course to e-learning platforms; some of them have even created innovating platforms now used worldwide; others play an important part in the definition of public policies related to e-learning use, especially concerning training for the unemployed and workers in activity. Common research projects, carried on by public authorities and research centres aim at exploring specific dimensions of e-learning practices, such as the motivation of the participants to continue a course, barriers to the adoption, etc., and to draw some the conclusions useful for the general diffusion of the tools. Their exists a very differentiated uses of e-learning between institutions, reflecting both particular internal dynamics, and choices of platforms and, therefore, training strategies. We refer for the complete list to the "Virtual campus Initiatives list beneath this page.

Contributing to the development of e-learning is also very present in other universities, such that of Universiteit van Gent and Vrije Universiteit Brussels which collaborate very narrowly in the development of the open source e-learning platform called “Dokeos”. This platform has been based initially on the Claroline source code but is now having its own way. The Dokeos solution is currently used in many institutions, and is controlled at the present time by a private company based in Brussels. The software is targeted either to university and high schools uses but also other diversified customers (administrations, companies, projects, etc).

If the e-learning forms now part of the life of all the Belgian universities, this mode of training also gradually penetrated the activity of other training operators, such as the

organizations of vocational training. Those are often helped by the university research centers to develop their strategies, to conceive and coordinate projects, to provide support in the

development of contents.

The principal actors on the matter are the public organizations in charge of training for the unemployed. The practice of self-tuition indeed constitutes a traditional tool often used historically as a mean of training. Since the end of the year 2006, the Walloon Agency of Telecommunication (AWT), became the public authority in charge of the global coordination of the e-learning offer for the Walloon region. The AWT carry on this activity within the framework of a regional program (program Prométhée II), whose objective is to develop economic activity through the ICT appropriation by the greatest number. This program gathers the DG of the research of the Walloon region (DGTRE), Forem and the Centers of competences specialized in ICT.

Similar strategies are also pursued by the VDAB – Vlaasmse Dienst voor Arbeidsbemiddeling in Beoepsopleiding – and the ORBEM – Office Régional Bruxellois de l’Emploi –, both in charge of training for the unemployed for the Flemish and Brussels region, although their specific contexts (in particular the kind of grid of centers of competences) differ. The platforms of development selected are also different (Lotus CMS for the VDAB; NetG for ,Brussels Formation (ORBEM)), which makes the exchange of contents difficult.

Connectivity

BELNET is the Belgian national research network that was established in 1993 as part of the Federal Science Policy Office. With its network, that has an extremely high capacity, BELNET guarantees Belgian universities, recognised research centers, and educational establishments the very best possibilities with regard to Internet connection and use of the research network. Since 1995, Belgian public bodies and departments can also make use of the services of BELNET.

At present, approximately 625.000 end users in more than 185 Belgian institutions have a high-speed Internet connection via BELNET.

In addition, BELNET manages the Belgian Internet exchange BNIX ("Belgian National Internet Exchange"). This node is a centralised infrastructure that enables Internet Service Providers (ISPs) active in the Belgian market to exchange traffic between one another. Thanks to BNIX, the traffic between Belgian Internet users does not have to make a detour over any foreign countries.

Relevant organisations

RESTODE is the pedagogical server/portal, organised by the French Community of Belgium. It is the acronym for (in French) RÉSeau Télématique de l'Organisation Des Études (Telematic resources for the organisation of education) and contributes, through its own resources and the Internet, to the realisation and implementation of educational and pedagogical projects in the French Community’s educational field. One of its objectives is to encourage the development and use of ICT applied to education. It proposes among others to provide a data base with pedagogical documentation (pedagogical resources such as articles, a list of pedagogical servers by country and notebooks for different subject matters).

Source http://www.restode.cfwb.be

ICT in education initiatives

ICT Initiatives in the French Community - 'The WIN Project'

The Walloon government in June 1996 passed the Win Project (Wallonie Intra Net), initiated by the Ministry of National and Regional Development, Equipment and Transport. In July 1997, its implementation phase agreement was signed. In November of the same year, the telecommunications chapter of the ‘Complementary Regional Political Declaration’, published by the Walloon government in November 1997, introduced a very precise program of action, which aimed to develop the use of telecommunication services as well as the cultural integration of ICT into the social and economic life of Wallonia.

In February 1998, the Walloon Region signed an agreement of cooperation with the French Community and the German Community. The agreement was based on the following principles:

- Belgium is intent on boosting its economy;

- The development of telecommunications is a major objective of this policy;

- The effective implementation of this policy requires young people to be trained in the use of ICT;

- The use of ICT by students, within different schools, is a new resource for learning and a necessary condition for a policy of equity.

The agreement was thought to require the following to meet the imminent changes:

- Active support to be given to providing computer equipment throughout schools, so allowing each student to be trained in the use of ICT;

- The training of personnel, including one resource-person for each school;

- The establishment of educational servers so that each school has access to Internet;

- The establishment of one organization to supervise the deployment of equipment, and to ensure the development of this equipment. This work also required re-evaluating and renewing materials intended for teaching and learning purposes.

ICT in Primary and Secondary Schools in Wallonia

In 1998, Minister/President of the French Community both in Wallonia and in the Brussels Region finalised a plan to provide ICT facilities and the training of young people in the use of new information and communication technologies, through the famous Win Project (Wallonie Intra Net). A resource person for this purposes was appointed for each school in the both regions (Wallonia and Brussels) not only as a priority in boosting the economy, but also as compulsory incorporation into the education system. Therefore, the main aim is the determination to develop a policy that guarantees equal opportunities and ensuring that all pupils and students can secure access to ICT during the time of their education.

The strategy used is quite innovative. It is not the introduction of ICT as a core subject, but rather the incorporation of ICT into the vary many different subjects and disciplines, teacher training and other professional and vocational trainings, as well as the provision of multimedia equipments.

Each region, Wallonia and Brussels, provides computers and telecommunication equipments to their respective schools and the idea was that they were also going to maintain and provide insurance for them for three years against theft, damage and deterioration.

In Wallonia, this scheme was originally managed by the Ministry of Technical Equipment and Transport (MET) while in Brussels it was controlled by the Computer Center for the Region of Brussels (CIRB). The private partner in this initiative, Belgacom, offers preferential rates for internet access to schools via I-line.