Welcome to the Virtual Education Wiki ~ Open Education Wiki

Netherlands

by Theo Bastiaens for Re.ViCa. Updated by Daniela Proli and Nikki Cortoos

For general and HE-related material see Netherlands from Re.ViCa

For entities in the Netherlands see Category:Netherlands

For other countries within the Kingdom of the Netherlands see Category:Netherlands - realm

Partners and Experts situated in the Netherlands

Theo Bastiaens, who was a partner in Re.ViCa

The Netherlands in a nutshell

The Netherlands (Dutch: Nederland) is the European part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, which consists of the Netherlands, the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba in the Caribbean. The Netherlands is a parliamentary democratic constitutional monarchy, located in Western Europe. It is bordered by the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east.

The Netherlands is often called Holland. This is formally incorrect as North and South Holland in the western Netherlands are only two of the country's twelve provinces. Still, many Dutch people colloquially refer to their country as Holland in this way, as a synecdoche.

The Netherlands is a geographically low-lying and the 25th most densely populated country in the world, with 395 inhabitants per square kilometre (1,023 sq mi)—or 484 people per square kilometre (1,254/sq mi) if only the land area is counted, since 18.4% is water. The population in total is 16.3 million.

The Netherlands has an international outlook; among other affiliations the country is a founding member of the European Union (EU), NATO, the OECD, and has signed the Kyoto protocol. Along with Belgium and Luxembourg, the Netherlands is one of three member nations of the Benelux economic union. The country is host to five international (ised) courts: the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, the International Criminal Court and the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. All of these courts (except the Special Tribunal for Lebanon), as well as the EU's criminal intelligence agency (Europol), are situated in The Hague, which has led to the city being referred to as "the world's legal capital."

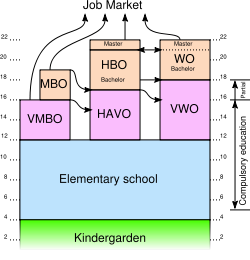

Education in the Netherlands

Compulsory education (leerplicht) in the Netherlands starts at the age of five, although in practice, most schools accept children from the age of four. From the age of sixteen there is a partial compulsory education (partiële leerplicht), meaning a pupil must attend some form of education for at least two days a week. Compulsory education ends for pupils age eighteen and up.

Basisonderwijs - Primary education

Between the ages of four to twelve, children attend basisschool (elementary school; literally, basisschool). This school has eight grades, called groep 1 (group 1) through groep 8. School attendance is compulsory from group 2 (at age five), but almost all children commence school at four (in group 1).

Voortgezet Onderwijs - Secondary Education

On leaving primary school basisonderwijs at the age of about 12 (after eight years of primary schooling) children choose between three types of secondary education (voortgezet onderwijs) :

- VMBO (pre-vocational secondary education or voorbereidend middelbaar beroepsonderwijs: four years)

- HAVO (senior general secondary education or hoger algemeen voortgezet onderwijs: five years)

- VWO (preuniversity education or voorbereidend wetenschappelijk onderwijs: six years).

Most secondary schools are combined schools offering several types of secondary education so that pupils can transfer easily from one type to another. All three types of secondary education distinguish between the lower years and the upper years. In the lower years the emphasis is on acquiring and applying knowledge and skills, and delivering an integrated curriculum. Teaching is based on attainment targets which specify the knowledge and skills pupils must acquire. In the first two years of secondary school, 1,425 real hours per year must be spent on the 58 attainment targets. The school itself translates these targets into subjects, projects, areas of learning, and combinations of all three, or into competence-based teaching, for example. Besides English, which is compulsory for all pupils, those in HAVO and VWO study two other modern languages, while pupils in VMBO study one.

VMBO There are four learning pathways in VMBO:

- basic vocational programme;

- middle-management vocational programme;

- combined programme;

- theoretical programme.

After completing VMBO at the age of around 16, pupils can go on to secondary vocational education (MBO). Pupils who have successfully completed the theoretical programme within VMBO can also go on to HAVO. HAVO certificate-holders and VWO certificate-holders can opt at the ages of around 17 and 18 respectively to go on to higher education.

HAVO is designed to prepare pupils for higher professional education or hoger beroepsonderwijs (HBO). In practice, however, many HAVO school-leavers also go on to the upper years of VWO and to secondary vocational education middelbaar beroepsonderwijs.

VWO is designed to prepare pupils for university. In practice, many VWO certificate-holders enter HBO. MBO certificate-holders can go on to higher professional education, while HBO graduates may also go on to university.

In addition to mainstream primary (basisonderwijs) and secondary schools (voortgezet onderwijs) there are special schools (speciaal onderwijs) for children with learning and behavioural difficulties who – temporarily at least – require special educational treatment. There are also separate schools for children with disabilities of such a kind that they cannot be adequately catered for in mainstream schools. Pupils who are unable to obtain a VMBO qualification, even with long-term extra help, can receive practical (trainingpraktijkonderwijs), which prepares them for entering the labour market.

Young people aged 18 or over can take adult education courses or higher distance learning courses.

Vervolgonderwijs

Mbo (middelbaar beroepsonderwijs, literally, "middle-level vocational education") is oriented towards vocational training. Many pupils with a vmbo-diploma attend mbo. Mbo lasts three to four years. After mbo, pupils can enroll in hbo or enter the job market.

Hbo

With an mbo, havo or vwo diploma, pupils can enroll in hbo (Hoger Beroeps Onderwijs, literally higher professional education). It is oriented towards higher learning and professional training, which takes four to six years. The teaching in the hbo is standardized as a result of the Bologna process. After obtaining enough credits (ECTS) pupils will receive a 4 years (professional) Bachelor's degree. They can choose to study longer and obtain a (professional) Master's degree in 1 or 2 years.

Wo

With a vwo-diploma or a propedeuse in hbo, pupils can enroll in wo (wetenschappelijk onderwijs, literally scientific education). Wo is only taught at a university. It is oriented towards higher learning in the arts or sciences. The teaching in the wo, too, is standardised due to the Bologna process. After obtaining enough credits (ECTS), pupils will receive a Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science or Bachelor of Laws degree. They can choose to study longer in order to obtain a Master's degree of different fields. At the moment, there are three variants: Master of Arts, Sciences, and Master of Laws. A theoretical Master typically lasts one year, however the majority of practical (e.g. medical), technical and research Masters require two or three years.

Education for sick children

Since the decree on support of education for sick students of 1 August 1999 (Ondersteuning Onderwijs Zieke Leerlingen (WOOZL)), hospital schools were disbanded in the Netherlands.

The network Ziezon was set up in 2000 for the 130 teachers of these hospital schools and their co-ordinators, to maintain and further develop their expertise, as well as to organise events and implementing ICT resources. Today Ziezon is a network that is there for anything to do with providing education to the ill.

Schools in the Netherlands

Further and Higher education

There are two types of higher education in the Netherlands (see also above). The universities prepare students for independent scientific and scholarly work in an academic or professional setting. The hogescholen are universities of applied sciences that prepare students for a wide variety of careers in seven sectors: agriculture, engineering and technology, economics and business administration, health care, education/teacher training, social welfare, and fine and performing arts. This type of higher education is known in Dutch as HBO (hoger beroepsonderwijs). At present there are 14 universities in the Netherlands and 45 universities of applied sciences.

The differences between the universities of applied sciences and the research universities have become less marked in the course of time. Nevertheless, a number of differences remain. Universities of applied sciences offer four-year programmes, leading to a Bachelor's degree, which are strongly geared towards practical training. The programmes focus on specific occupations and include traineeships or work placements that provide students with practical work experience. Universities of applied sciences also offer an increasing number of programmes that lead to a Master's degree.

Universities in the Netherlands

For a full list, visits http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_universities_in_the_Netherlands

Polytechnics in the Netherlands

Colleges in the Netherlands

Education reform

Schools

Since 2007, Dutch education policy has been the result of a process of increased collaboration within the field of education as represented by sector organizations. The national government makes policy and budget agreements with these organisations according to the formulated sector policy plans. Sector organizations also take the lead in proposing innovative initiatives to reform education in the Netherlands

Curriculum reforms

In the Netherlands there is no national curriculum. The structures as well as the content of school curricula are the responsibility of the schools themselves. The Ministry of Education, Culture and Science only sets the final objectives students should achieve. At national level it has been agreed that in the future schools need to modify their curriculum due to the changing population of students, representing a broader ethnic diversity. New curricula should include lessons for “citizenship”, as well as an increased focus on language and mathematics. Schools are also asked to develop excellence programmes for students with high potential.

Quality-centred agenda for school

Between 2007 and 2008, the government launched three quality-centred agenda respectively addressing Primary education: the agenda ‘Schools for tomorrow’ gives priority to improving children’s language and numeracy skills, since competence in this area is essential to their success in other subjects at school, in their further school career and in society at large.

- Secondary education: the quality centred long range agenda addresses, addressing education’s contribution to society and aiming to strengthen both the quality of education and its role in the community.

- Upper secondary and post-secondary education

- Secondary vocational and adult education: the strategic long-range agenda focuses on increasing the quality of vocational education to augment the transition from education to the job market. It also introduces competence-based vocational education.

A far as vocational education in concerned, in 2009 the 'Deltaplan' has been set up which aims to improve the language and maths skills of students in this educational path. There is also an agenda that aims to improve the international status of vocational education, focusing on for example mobility and international cooperation.

Reforms affecting teachers

Due to the growing shortage of teachers in primary and secondary education in the last few years, in 2008 the Dutch Ministry of Education signed a covenant, “Teacher of the Netherlands”, which proposes measures to improve the working conditions and remuneration of teachers. More services are offered to assist the further professionalisation of teachers in 21st century skills through public ICT organisations and pedagogical centres. In addition, more training programmes are offered to university graduates working in various domains (outside schools), to attract them into teacher training.

More personalised learning paths

One of the priority of the dutch education policy formulating measures to “tailor education” in accordance with the personal ability, social network and interests of the student. Teaching programmes that use ICT to enable tailored education are being developed and promoted by various institutions. The Ministry facilitates open learning resources (e.g. Wikiwijs, see below) to assist teachers to develop digital learning materials for students with different educational talents and needs. To assist the teacher to develop individual learning models, virtual learning communities of teachers are being built (Leraar24) that facilitate the exchange of ideas and experiences between teachers.

Support to initiatives for weak and excellent students

the Dutch Ministry of Education finances extra programmes and activities for both weak and excellent students. The OECD report (OECD, 2008) shows that Dutch Education is doing well for middle-range students but scores inadequately for students at the bottom and at the top of educational achievement. Accordingly, new additional programmes focus more on language and mathematic lessons serving weak students and excellence programs serving top talents.

Support to innovation

the Dutch Government stimulates the innovative power of the educational field by inviting tenders for innovative projects. Schools can submit an innovative proposal to solve key educational challenges, such as “finding skilled teachers” or “stimulating ICT use in education”.

Post-secondary

Higher Education

A guaranteed standard of higher education is maintained through a national system of legal regulation and quality assurance at the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. Since 2002, institutions offering higher education are assessed and accredited by the Accreditation Organization of the Netherlands and Flanders (NVAO or Nederlands-Vlaamse Accreditatieorganisatie). All degree programmes offered by research universities and universities of professional education will be evaluated according to established criteria, and those that meet the criteria will be accredited, that is, recognised for a period of six years. Only accredited programmes can issue legally recognised degrees and are eligible for government funding. Only students enrolled in an accredited programme receive financial aid. All accredited programmes are listed in the publicly accessible Central Register of Higher Education Study Programmes (CROHO). Naturally, institutions are autonomous in their decision to offer non-accredited and non-funded programmes, subject to internal quality assessment.

Administration and finance

Schools

Education policy is coordinated by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, together with municipal governments. A distinctive feature of the Dutch education system is the combination of a centralised education policy with decentralised administration and management of schools. In August 2006 the government introduced block grant funding in primary education in order to give schools more freedom in terms of spending. School boards have been given a certain budget and the freedom to decide on the spending. For secondary education block grant funding was introduced in 1996.

Central government controls education by means of regulations and legislation, taking due account of the provisions of the Constitution. Its prime responsibilities with regard to education relate to the structuring and funding of the system, the management of public-authority institutions, inspection, examinations and student support. Central government also promotes innovation in education. The Minister is, moreover, responsible for the coordination of science policy, emancipation policy of women and gays and for cultural and media policy. There are public, special (religious), and private schools. The first two are government-financed and officially free of charge, though schools may ask for a parental contribution (ouderbijdrage). Public schools are controlled by local governments. Special schools are controlled by a school board. Special schools are typically based on a particular religion. There are government financed Catholic and Protestant elementary schools, high schools, and universities, furthermore there are government financed Jewish and Muslim elementary schools and high schools. In principle a special school can refuse the admission of a pupil if the parents indicate disagreement with the school's educational philosophy. This is an uncommon occurrence. Practically there is little difference between special schools and public schools, except in traditionally religious areas like Zeeland and the Veluwe (around Apeldoorn). Private schools do not receive financial support from the government. There is also a considerable number of publicly financed schools which are based on a particular educational philosophy, for instance the Montessori Method, Pestalozzi Plan, Dalton Plan or Jena Plan. Most of these are public schools, but some special schools also base themselves on any of these educational philosophies.

Post-secondary

Quality assurance

Schools

In the Netherlands the Education Inspectorate (Onderwijsinspectie) is responsible for supervising the education system as a whole and the performance of the individual schools and educational institutions. All institutions in primary, secondary and special education, as well as in vocational and adult education are regularly visited and evaluated. The inspectorate applies the same standards for schools with a public board and schools with a private board, the latter of which are the vast majority in the Netherlands. The basis for the supervision is a rating framework consisting of the thirteen quality aspects named in the Education Supervision Act and the attached indicators and points of attention ( see https://www.onderwijsinspectie.nl). The use of ICT is integrated within these indicators. These frameworks are set up in consultation with representatives of the education sector and require the approval of the Minister of Education (article 12 of the above-mentioned Act). A distinction is made between quality aspects that concern the results of the education provided and those that concern the teaching-learning process. Within the framework, indicators are designated that measure the core elements of education quality. These “key indicators” form the basic set for the so called Periodic Quality Assessment (PQA). This model of supervision is conducted once every four years at all educational institutions. Under the Education Inspection Act the duties of the Inspectorate are:

- to assess the quality of teaching on the basis of checks on compliance with legislation;

- to monitor compliance with legislation;

- to promote the quality of teaching;

- to report on the development of education;

- to perform all other tasks and duties required by law.

Under the Primary Education Act (WPO), the Secondary Education Act (WVO) and the Adult and Vocational Education Act (WEB), school boards bear primary responsibility for ensuring the quality of teaching. As the competent authority, they are the point of contact for inspections. Wherever possible, risk analyses are conducted on the basis of existing information. The Inspectorate will not ask for supplementary information unless risks are identified and a further inspection is considered necessary. A report of the Inspectorate’s findings is sent to the school or institution concerned, to the Minister and State Secretaries, and to parliament.

Quality assurance in ICT integration in schools

The Ministry of Education regards monitoring the development of ICT in education as very important and requires this process to be conducted annually. AN annual ICT monitor is carried out by Kennisnet, the dutch foundation which supports school in primary, secondary and vocational education in integrating ICT in their school policies The monitor collects data on key factors or indicators that are known to influence the efficient and effective use of ICT in education. The conceptual framework for the monitor is derived from the so-called Four in Balance model, which reflects a research-based vision of the introduction and the use of ICT in education. The core premise underlying the Four in Balance model is that use of ICT for educational purposes in schools depends on maintaining a balance between four building blocks:

- the vision relating to education and ICT;

- knowledge and skills of teachers;

- educational software (including content);

- ICT infrastructure.

Data for this monitor are collected from a representative sample of school boards, school management, teachers and students by both the Dutch inspectorate for education and several research institute.

The latest report published by Kennisnet is the Four in Balance Monitor Report 2010

Post-secondary

Information society

In the Netherlands, access to online information is not only supported by a high diffusion of internet connections, but also by many organisations, businesses and (increasingly) citizens providing online content. Moreover, the Dutch government contributes to a high quality of available information, supports the European Safer Internet Programme and is in favour of net neutrality, the principle of letting all internet traffic flow equally and impartially, without discrimination.

The government bears some responsibility for internet safety, taking a leading role compared to industry and schools. In 2008 the government, in collaboration with business, started the programme Digivaardig & Digibewust, the Dutch programme promoting e‑awareness, e‑inclusion and e‑skills. This programme aims at the e‑inclusion of all Dutch people by promoting safe internet use and media literacy.

In line with the liberal values in Dutch society the government is committed to the freedom of expression in the online environment, as elsewhere, as long as these expressions stay within the limits of what is legally acceptable (see the section on the legislative environment below). This also holds for the protection of privacy on the net. Although there is fairly little concern among citizens about threats to their privacy, the data protection law is available to penalise the abuse of personal information.

The Dutch government is seeking to use ICT tools to reduce administrative burdens and improve service delivery. Internationally, the Netherlands is at the forefront in these tasks. In line with the traditional Dutch focus on participative and inclusive government, featuring broad citizen consultation and involvement, the Netherlands has developed ambitious programmes and activities that aim to increase user take-up of e‑services.[7] In order for citizens to reach a fast, efficient and customer-focused government, policy is directed towards the development of a basic infrastructure, which includes electronic access to the government, e‑authentication, basic registration and services (e.g., applying for a passport). However, the take-up of e‑services is rather slow, partly due to insufficient skills of the Dutch, and also due to a lack of user orientation in e‑government services.

A strong new trend is the rise of Web 2.0, leading to a substantive deepening of existing internet use and means that people will begin making use of various kinds of different content. Because the content created by users is not constrained to textual information, audiovisual information is added in increasing amounts to the web as music and self-made film clips are shared with others. In the Netherlands the social networking site Hyves has attracted many people, in particular the youth. As is the case elsewhere in the world, Twitter is the latest fashion in information exchange.

Web 2.0 also creates opportunities for musicians and other artists to offer (trailers of) their music and other forms of creative expression on the net. MySpace is currently a popular website in the Netherlands, where large numbers of users maintain weblogs and profiles.

Another but related trend is the improvement of media literacy. In the Netherlands media literacy is often called “media wisdom”, which refers to the skills, attitudes and mentality that citizens and organisations need to be aware, critical and active in a highly mediatised world. Most Dutch media education initiatives are directed at the internet and audiovisual media. However, the converging of different media platforms makes it hard to distinguish separate media. TV, mobile and internet are converging, and virtual worlds and “real” worlds also seem to be merging.

Action steps

Some of the main issues that need special attention in the future are:

- Media literacy: In October 2006 the Dutch cabinet stressed the importance of this topic and saw the need for a centre of media expertise and a code of conduct for the media. The centre was established in May 2008. Many different organisations are involved in activities that aim to achieve the goal of increasing media literacy.

- Identity management: Due to a combination of technological and social developments we can see an increasing convergence of new technologies and services. Steps need to be taken in order to support the identity management of citizens and to increase their sense of online security.

- Improved internet safety: Cyber bullying, cyber crime (hacking, phishing, viruses, etc.) and inappropriate and illegal content are prolific. Good organisations and campaigns have already been established. However, this is an ongoing task and there is still work to be done.

Sourced from Access to online information and knowledge 2009, country report on the Netherlands

ICT in education initiatives

ICT policy for education in the Netherlands is set out by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, while the Kennisnet Foundation supports schools in primary, secondary and vocational education in implementing ICT in their school policies. Schools in the Netherlands are in fact themselves responsible for the implementation of ICT in education and each institutions has to design a vision, mission and strategy around the implementation and the use of ICT in schools.

In the Netherlands the developments in ICT policy have evolved into a strategic approach to ICT as a means of stimulating and supporting the learning process. This instrumental approach is aimed at understanding the effects of ICT in relation to educational/pedagogical use to ensure the effective and innovative use of ICT throughout learning. Currently, a lot of attention is directed towards the integrated use of ICT in the primary (teaching) and secondary (administration) educational processes. The character of ICT policy is, therefore, much more focused on understanding and describing ICT is an instrument that could be efficiently woven or blended as well as anchored into teaching and learning processes and creating a knowledge society. Consequently, ministerial policies in the last few years have been geared towards the optimal integration of ICT in innovative learning processes. ICT and ICT policies are seen as a part of educational policy and no longer as a separate policy. Executive organs like the Kennisnet Foundation (for primarym, secondary and vocational education) and Surf Foundation (for higher education), the national pedagogical centres and sector organisations set up programmes, projects and action plans to serve the needs and demands of the schools. These plans focus on three main issues:

- professionalisation of the teacher;

- the school as an organisation with an overall view concerning the integration of ICT;

- optimal use of digital learning material.

Although the Dutch Ministry of Education and Culture no longer considers ICT to be a separate policy, it supports specific ICT multiannual national programmes. These programmes aim to provide a broad impulse regarding specific ICT issues as formulated by the schools themselves or sector organisations. Some examples of these programmes are:

Media literacy

In 2007 the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science set up an expertise centre for Media Literacy. This centre works together with more than 140 organisations, varying from publishers to libraries and broadcasting institutions. The objective of this programme is to increase knowledge of and the necessary competences in the prudent use of new media.

Stimulating the use of digital learning material

This programme was initiated in 2008 to stimulate increased use of digital learning material in primary, secondary and vocational education. An important part of the programme includes activities to form a well-functioning market of digital learning materials. To this end, the available digital learning materials are assembled and connected to portals and platforms that are easily accessible for teachers. Through public platforms, demand for and supply of the digital learning materials are matched and the materials made readily available for a specific target audience. The programme also provides research information available about the popularity, user-friendliness and efficacy of different digital learning materials.

Stimulating learning platforms for teachers

In order to support teachers in their professionalisation with the use of ICT, an online platform was created in 2009 (www.leraar24.nl). The platform includes files and videos on various educational subjects supplied by teachers themselves. At this platform teachers can learn from each other’s experience, share their methods and discuss the key issues that they are concerned with.

Stimulating digital learning environments

Dutch schools make increasing use of digital learning environments. The Ministry of Education, Culture and Science initiates digital learning environments for specific target audience. In 2009 the acadin learning environment for excellent (gifted) pupils in primary education was set up. This learning environment provides information about giftedness for parents, pupils and teachers. Pupils and teachers also use the environment as part of their teaching and learning programme.

Innovation programmes

SURFnet and Kennisnet have been collaborating in the SURFnet/Kennisnet Innovation Programme since 2004. The project aims to enrich education through innovative and practical ICT applications relevant to the entire educational process. Within this framework a variety of products and services have been developed, including Make a-Game, Expert op Afstand (remote expert), Teleblik, Video portal, and Expose Your Talent.

Virtual initiatives in schools

Platforms for teachers

As mentioned above, the dutch government supports as a priority the use of digital resouces and the development of learning platforms for teachers, in the wider framework of professionalisation of teachers in integrating ICT in education through innovative methods. The most prominent platform in the Netherlands are the following

Wikiwijs is an open educational resources (OER) platform for teachers launched by the Dutch Ministry of Education to

- stimulate development and use of OER,

- improve access to both open and 'closed' digital learning materials

- support teachers in arranging their own learning materials and professionalisation

- increase teacher involvement in development and use of OER.

Wikiwijs is focused on all levels of education, from primary to higher education. All teachers have open access to these digital material banks. The material is easy searchable, retrievable and usable thanks to its classification according to school level and subject. A forum is also available as well as rating functions, enabling teachers to advise each others on the most adequate materials available.

see above

Teleblink is a website that assembles thousands of hours of educational television and makes these available online, free of charge to schools. Teachers can download and upload films and animations and give their opinion about particular material, after logging in with their school accounts.

Acadin.nl

Acadin.nl is a digital learning environment provided by the Acadin Foundation, a non-profit organisation, subsidised by the government which supports teachers of gifted students in primary education. The primary goal of Acadin is to develop custom made online educational programs for gifted children and to provide guidance to teachers. Acadin contributes to the education of gifted students by offering educational opportunities to their needs, namely challenging learning activities and a guiding program for thier teachers. Acadin is also a meeting place for student, teachers and experts, including forum and a messaging system

Virtual Music School

The virtual music school is a learning environment which was tested in the Utrecht Conservatory where it is now incorporated in the first year of a four year curriculum, and used during school time. Students can repeat lessons at their will and at their own pace.

The Edufax virtual classroom

Edufax is a dutch private company supplying educational consultancy, language courses and distance education to children and adults living temporarily in all four corners of the world. Since 1992 Edufax has been supporting HR managers and families in all aspects of educational development during their years as expatriates. in 2010 Edufax using the internet for teaching Dutch language and culture to all of its 700 students between the ages of six and 18.

Edufax students find more than just lessons on their site. The homepage looks rather like the front page of a newspaper, with a lot of news from the Netherlands. The students also have the option of posting their own stories and opinions. They can also use the site to contact other Dutch expat children of their own age. They can, for instance, work together on assignments through a forum.

see http://www.expatica.com/nl/education/school/The-virtual-classroom_16680.html

The Wereldschool

The Wereldschool (World school in English) is a private company providing teaching programmes for Dutch-speaking children between 3 and 16 years old who are going abroad with their parents for an extended period of time. Pupils enroll in teaching programmes specifically for their school level (primary school or three secondary school levels) or a specific course such as IB Dutch and language courses. Approximately 1,400 pupils per year enroll, spread over more than 128 countries. The school's programme corresponds to the Dutch curriculum so that re-integration in Dutch schools after returning to the country is possible.

Support for sick children

More than 250.000 children in the Nederlands are chronically ill. Since the law on educational support for sick students of 1 August 1999 (Ondersteuning Onderwijs Zieke Leerlingen (WOOZL)), hospital schools were disbanded in the Netherlands and the reponsibility to provide obligatory education and councelling of sick children falls on to each invididual school. A few initiatives help them to provide the support to continue educating these children:

Ziezon

Ziezon, the Rural network Illness and Education (landelijk netwerk ziek zijn & onderwijs) is a network of teachers, consultants, advisers and others who work with sick children in their homes. It is supported by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

The general goal of teaching support to sick pupils in University Hospitals is aimed at continuation of education, as a means to help sick pupils re-enter school and prevent feelings of isolation. Educational support of sick pupils includes more than teaching parts of the curriculum, and Ziezon makes use of Webchair, videoconferencing hardware to enable sick children to virtually attend a class and keep contact with their classmates.

Webchair is a Dutch private company that provides the 'webchairs' (hardware) for this.

Stichting Digibeter

Stichting Digibeter (Foundation Digibeter in English) enables children, who cannot attend school in person for a prolonged period of time due to illness or a handicap, to connect children with their class so they maintain contacts and can continue their education.

Virtual initiatives in post-secondary education

EMINUS project at the REA college

REA college (vocational training for people with a physical disability) provides virtual classroom through which students with disability which would find difficult to move to school everyday can be trained at home for jobs that they can easily carry out from their homes. Eminus, the name of the project, is in fact the Latin term for ‘on a distance’ or ‘at a distance’. EMINUS includes virtual classes of four students per teacher, interactive communication and live presentations of lessons and aims to get as close as possible to regular education. Fast internet connections and streaming video allow for non-verbal communication – such as body language or even sign language – which is essential for getting a message across. The initiative also enables students to take part in social activities. For example, they will be missed if they are not present online. They can find and talk to each other just as though they were in a school yard.

Information in english can be retrieved at http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/areas/socialcohesion/egs/cases/nl004.htm

Lessons learnt

General lessons

Some remarks on virtual schooling in NL (2006) can be sorted from “The memory of the Netherlands: introducing culturale heritage into the new teaching-learning environment” by Olivier Nyirubugara. The author pinpoints the following:

- “It is true that virtual secondary schools are proliferating in vast countries like the United States and Australia, where pupils have to travel long distances before they can reach their schools. As Durkheim (1922, p.11) suggests, each educational system is modeled on each country’s social specificities and needs, to which geographic constraints could be added. In a country like the Netherlands, where the home-to-school distance is not a preoccupation, virtual schooling at the primary or secondary school levels would not appear on the priority list of educational policy makers. Instead, during the reflection period, educationalists and policy makers should discuss the cohabitation in real classes of Digital History and ‘conventional methods.’ Given the average ratio of one computer for ten students not even in classrooms but rather in the computer rooms or the library, it would be unthinkable to envisage a digital-only classroom as it is almost the case in Sweden..."

Notable practices

References

- Eurydice, National summary sheets on education systems in Europe and ongoing reforms, The Netherlands 2010

- Organisation of the education system in the Netherlands 2008/09

- EUN, The Netherlands, ICT in Education - Country Report

- Access to online information and knowledge 2009, country report on the Netherlands

- Kennisnet 2010, Four in Balance Monitor Report

- Wikipedia, Education in the Nederlands

- Eurybase, The Information Database on Education Systems in Europe: The Education System in the Netherlands, 2008/09

Recent reports (last 8 years)

- Bacsich, P. (2017), Credit Transfer for Open/Online Graduate Programs: Annex 6 Netherlands, Report for Thompson Rivers University, September 2017, Media:PLAR Masters benchmark Annex 6 Netherlands.pdf

>> Main Page

For OER policies and projects in Netherlands see Netherlands/OER