Welcome to the Virtual Education Wiki ~ Open Education Wiki

Estonia

by Jüri Lõssenko of EITF

For entities in Estonia see Category:Estonia

Partners situated in Estonia

Estonian Information Technology Foundation

Estonia in a nutshell

(mainly sourced from: Wikipedia and OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education – Country Background Report for Estonia.)

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia is a country in Northern Europe in the Baltic region. Its territory covers only 45,227 km² and is divided into 15 counties. Estonia is a democratic parliamentary republic. Its capital and largest city is Tallinn. Estonia was a member of the League of Nations from 1921, has been a member of the United Nations since 1991, of the European Union since 2004 and of NATO since 2004. With only 1.4 million inhabitants, Estonia comprises one of the smallest populations of the EU countries.

In 1918, the Estonian Declaration of Independence was issued, to be followed by the Estonian War of Independence (1918-1920), which resulted in the Tartu Peace Treaty recognizing Estonian independence in perpetuity. During World War II, Estonia was occupied and annexed first by the Soviet Union and subsequently by the Third Reich, only to be re-occupied by the Soviet Union in 1944. Estonia regained its independence in 1991 and it has since embarked on a rapid program of social and economic reform. Today, the country has gained recognition for its economic freedom, its adaptation of new technologies and as one of the world's fastest growing economies.

The official language in Estonia is Estonian, which belongs to the Finno-Ugric language family and is closely related to Finnish. Along with Finnish, English, Russian and German are also widely spoken and understood. The major minority language is Russian with its speakers making up about 30 % of the population. Russian-language education is provided in public and also in private schools at all levels: pre-school, basic and secondary schools, as well as vocational schools higher education institutions. About 24 % of all Estonian school children attend Russian-language basic and secondary schools. Some 10 % of higher education students study in Russian.

Education in Estonia

Estonian education policy

(mainly sourced from: The Estonia Page and OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education – Country Background Report for Estonia.)

The Estonian Constitution states that everybody has the right to an education. Attending school is compulsory for all school-age children to the extent established by law, and is free in general education schools established by state and local governments. In order to make education accessible, the state and local governments are financially responsible for maintaining the necessary number of educational institutions. The law allows the establishment and operation of other types of educational institutions, including private schools.

Everybody has the right to an education in the Estonian language. In an educational institution in which minority students predominate, the language is chosen by the educational institution. Education is under the supervision of the state.

The Education Act has established that the objective of education is:

- creating favorable conditions for the development of individuals, family, the Estonian nation, national minorities and Estonian economic, political and cultural life in the context of the world economy and culture;

- developing a law-abiding citizenry;

- providing conditions for continuing education.

A wide network of schools and supporting educational institutions has been established in Estonia. The Estonian educational system consists of state, municipal, public and private educational institutions. The Education Act states that in accordance with the UNESCO international standard of education classification, education has the following levels: pre-primary education, basic education, secondary education and higher education.

Each level has its established requirements, which are called the state educational standards and are presented together with state curricula. The curricula contain the mandatory study programs, time scheduled to cover the programs, and descriptions of compulsory knowledge, skills, experience and behavioral norms.

Estonian education system

(mainly sourced from: The Estonia Page and OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education – Country Background Report for Estonia.)

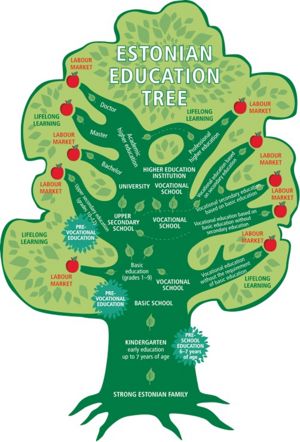

Basic education is established by a national curriculum of basic and secondary education. On the basis of the national curriculum, schools compile their own curricula. Basic education covers grades from one to nine. Basic education in Estonia is compulsory. Basic education is mainly taught at municipal schools (basic school classes at primary, basic and secondary schools). Local governments determine a service area for each school where it is obliged to guarantee all school-age children the opportunity to study.

Secondary education is voluntary and free at state and municipal educational institutions. General secondary education is acquired at upper-secondary schools (grades 10-12), and vocational education at vocational education institutions. Secondary education is governed by a national curriculum of basic and secondary education (general secondary education) or by a national vocational education curriculum and national curricula of vocations (vocational secondary education).

Access to higher education is regulated by the Universities Act and the Institutions of Professional Higher Education Act. Students having either a general secondary school-leaving certificate (12 years of schooling) or a secondary vocational school-leaving certificate (based on qualifications of different length) and the State Examination Certificate have access to higher education. In addition, those having a corresponding foreign qualification can gain access. But access for all students is subject to discretion of higher education institutions. Merit plays the dominant role in the access to the specific programs.

There are three types of educational institutions that provide higher education: universities (ülikool) - institutions of research, development, study and culture at all higher education levels in several fields of study; professional higher education institutions (rakenduskõrgkool) - educational institutions of professional higher education and Magister-study; and vocational education schools (kutseõppeasutus) - institutions of secondary vocational.

The different legal forms of HEIs are: public, state and private. Private institutions can be owned by a public limited company or private limited company entered in the commercial register or by a foundation or non-profit association entered into the non-profit associations and foundations register. Both public (or state) and private higher education institutions are authorized to operate.

Schools in Estonia

General education is divided into two parts: basic education (9 years: age 7 to 16) which is compulsory for all children in Estonia and secondary general education. Since 1993, the Basic School Leaving Certificate, obtained at the end of basic education, provides a student with the right to continue at the next level which offers two streams (in three further years): 1) Secondary general school/gymnasium education and 2) vocational education. Upon graduation of secondary general education, students obtain the Gumnaasiumi loputunnistus (Secondary School Leaving Certificate) which gives access to higher education.

Basic education is established by a national curriculum of basic and secondary education. On the basis of the national curriculum, schools compile their own curricula. Basic education covers grades one to nine. Basic education in Estonia is compulsory. According to the Education Act, every child reaching seven years of age on 1 October must attend school until basic education is acquired or until he or she is 17 years old. Basic education is mainly taught at municipal schools (basic school classes at primary, basic and secondary schools). Local governments determine a service area for each school where it is obliged to guarantee all school-age children the opportunity to study. In exceptional cases, basic education can also be acquired at home.

Secondary education is voluntary and free at state and municipal educational institutions. General secondary education is acquired at upper-secondary schools (gümnaasium, grades 10-12), and vocational education at vocational education institutions. Secondary education is governed by a national curriculum of basic and secondary education (general secondary education) or by a national vocational education curriculum and national curricula of vocations (vocational secondary education). Generally, about 95 % of those who graduate from day basic school go on to secondary schools; about 70 % of them to upper-secondary schools (gümnaasium); and 25 % to vocational schools.

Further and Higher education in Estonia

(mainly sourced from: OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education – Country Background Report for Estonia.)

See also the following OECD reports for more information about the Estonian higher education:

- Thematic Review of Tertiary Education - Country Reviews;

- Thematic Review of Tertiary Education - Country Background Reports.

In the period since the restoration of independence in 1991, remarkable changes took place in the system of Estonian higher education. This was visible not only in the rise in number of HEIs, but also in the development in the areas of funding, human resources management, quality assurance, research and innovation, equity, links to the labor market and internationalization.

The universities offer Bachelor (three years, 180 ECTS – or exceptionally 240 ECTS credits), Master (one-two years, 60-120 ECTS) and PhD programs (three to four years). Medicine, pharmacy, dentistry, veterinary medicine, architecture and civil engineering are exempted from the Bachelor-Master structure. These programs (still) have integrated tiers, leading directly to the Master degree (300-360 ECTS).

State professional higher education institutions offer mostly four-year Bachelor programs, but some programs are three years, some others four-and-a-half. Students can continue their studies at universities but often need bridging courses. The state institutions are allowed to offer Master programs (under some conditions) but, as of 2006 - 2007, there were only six Master programs registered by three state professional higher education institutions (Tartu Aviation College, the Estonian Maritime Academic and the Estonian National Defence College). Private professional higher education institutions offer mostly three-year programs, some offer Master programs as well.

Vocational education schools offer professional higher education programs. However, the recent Estonian Higher Education Strategy 2006-2015 envisages to close down most of these programs or to have the schools upgraded to professional higher education institutions.

In academic year 2005 – 2006, there were 39 HEIs in Estonia. Although the number of institutions seems high for a country the size of Estonia, this number has already been reduced due to the increase of quality and financial requirements in the legislation. In the course of the academic year 2006 - 2007, the number was further decreased to 35. The highest number of HEIs that the country has had was 49 in academic years 2001 – 2002 and 2002 – 2003.

Universities in Estonia

There are six public universities in Estonia: Tallinn University (with 7,350 students in 2005), the University of Tartu (18,536) – the oldest in the country (created in 1632), Tallinn University of Technology (10,700), the Estonian University of Life Sciences (4 752), the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre (567) and the Estonian Academy of Art (962). Although these institutions already existed in 1991, significant changes in their operation have occurred since then. Additionally, several of them have established a number of semi-independent (regional) colleges in the past 15 years. The public universities together catered for about two-thirds of the 68,287 students enrolled in Estonian HEIs in 2005.

There are five, relatively small private universities, most of which offer programs in just a few disciplines. The most important fields offered are business administration, law, media, arts and humanities and information technology. Their number of students in 2005 ranged from 116 to 2,547, in total they had 6,467 students. Eight professional higher education institutions constitute the public part of this sector catering for 7,142 students in 2005. Their size ranges from 166 to 2,111 students. Additionally, there are thirteen private professional higher education institutions (with a total of 7,452 students), all of very small size, although the largest of the privates is bigger than the largest public professional higher education institution (i.e. 2,538 students). Like private universities, also the private professional higher education institutions focus mostly on business administration, information technology, arts and humanities, but also on theology.

Polytechnics in Estonia

The third sector, vocational education schools, consists of six public institutions and one private institution. The total number of students in this sector is 4,359. They range in size from 30 to 1,322 students. These institutions offer not only tertiary education but also secondary-level education.

The governance of HEIs is under the auspices of the Ministry of Education and Research with three exceptions – The Estonian National Defense College (Ministry of Defense) and the Public Service Academy (Ministry of Interior Affairs). The Baltic Defense College (situating in Tartu) is operating under the agreement of three Baltic Ministers of Defense and is not part of the formal higher education system.

Colleges in Estonia

Education reform

Schools

Large majority of the school reform has centred around gradual shift in proportion of instruction in Russian language. After Estonia regained its independence in 1991, the number of pupils in Russian schools had risen to 35%. The Law on Basic and Secondary School, approved in September 1993, foresaw the transfer to Estonian-language instruction in all state and municipal gymnasiums by the year 2000, a target that quickly became unrealistic. The basic Russian-language schools had to give their students sufficient knowledge of Estonian for that purpose as well as facing an additional task of integrating other language speakers into the Estonian society.

As of the 2011/2012 academic year, Estonian will be the language of instruction in all upper secondary schools in Estonia. The schools can choose the Estonian curriculum or Estonian as a second language curriculum as the basis for teaching Estonian, and organize the state examination necessary for graduation according to the curriculum they have chosen (either a composition in Estonian or an examination in Estonian as a second language). The upper secondary school curriculum contains a minimum of 57 courses where Estonian is used as the language of instruction (one course equals 35 lessons).

The transition of compulsory subjects to Estonian language instruction in upper secondary schools where Russian has heretofore been used as the language of instruction has been gradual with each subsequent stage of the transition concerning pupils who start the 10th grade in the given academic year. Pupils starting the 10th grade in 2011 or later will have to study 60% of school subjects in Estonian.

There are 62 upper secondary schools with Russian as the language of instruction in Estonia, all of which will switch to Estonian language subject study in accordance with the schedule and procedure established in the regulation of the Government of the Republic. In basic schools, the owner of the school (generally the local government) will choose the language of instruction.

Post-secondary

(mainly sourced from: OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education – Country Background Report for Estonia.)

Major developments in the Estonian higher education policy may be outlined in three phases. The first phase (1989 – 1995) implied separating from the Soviet system and building up a new legal framework. Much effort was also put in realizing the 1995 University Act, paving the way for the 1996 Standard of Higher Education. The second phase (1996 – 1999) saw the expansion of the higher education system in combination with the development of legal frameworks and quality assurance mechanisms for the different sectors. The third phase (2000 – 2004) indicated the next wave of reforms, hallmarked by the higher education reform plan 2002.

The most recent strategy document (2006 – 2015) was approved by the Government in June 2006. This Estonian Higher Education Strategy 2006-2015 addresses three main challenges for the sector in the coming years. First, the number of students entering higher education is expected to diminish by about 60 % by 2016. Second, there is a clear need to strengthen the international dimension of higher education institutions. Third, additional funding – both for infrastructure and human resources – is of vital importance for the sustainability of the system. Estonia was also among the countries that signed the Bologna Declaration in 1999.

Administration and finance

Schools and post-secondary

The majority of general education schools – 517 of 582 schools in 2008 – are municipal schools, while 31 schools are state schools and 34 are private schools. Of the state schools, 27 are for pupils with special needs and 4 are ordinary schools. This means that general education schools are mainly funded from the budgets of local governments.

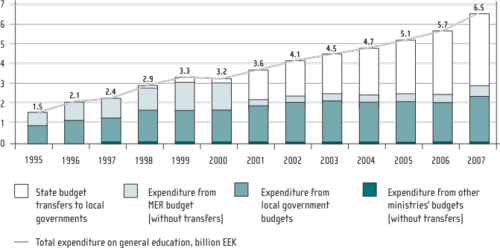

Local governments have the competence to establish, reorganize and close general education schools and to organize the transportation of pupils to and from schools, catering during study periods, etc. Support for covering education expenditures is allocated to rural municipalities and cities from the state budget. Funds for ensuring the minimum wages and continuing education of teachers as well as allocations for investments1, school lunches and expenditures associated with textbooks and study aids constitute the majority of the support. Support is also provided on the same principles for private general education schools. The funds allocated to local governments for covering education costs in 2008 amounted to 3.274 billion EEK. Allocations for education expenses increased 14% when compared to 2007. In 2009, 3.049 billion EEK was allocated, marking a 7% decrease in the funding provided for education expenses compared to 2008. The cost of providing school lunches for basic school pupils in the 2008/2009 academic year amounted to 225 million EEK.

The total public expenditure on general education in 2007 amounted to 6.5 billion EEK, which demonstrates a considerable increase over the years of 2006 and 2007 (12% and 14%, respectively). The high growth rate is largely the result of the coalition’s endeavours to raise the minimum salary of teachers2 to the same level as the national average salary within four years. As a result of this, the minimum salary of teachers in general education schools increased by approximately 20% a year from 2006 to 2008 (23%, 18%, and 22%, respectively).

State budget allocations to the budgets of local governments constitute more than a half (57% in 2007) of the total expenditure in the area of general education. At the same time, the general education expenditure of local governments makes up 34% of their total expenditure. The relative importance of local governments in the public sector’s expenditure on general education has decreased over the years – the contribution of local governments to the funding of general education schools constituted more than half of the total expenditure until the end of the 1990s.

Higher education

(mainly sourced from: The Estonia Page and OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education – Country Background Report for Estonia.)

Estonian HEIs receive funding from the public budget for the provision of graduates (so-called state-commissioned places), for capital investment and for other expenditure (foreign aid projects, education allowances for students, library expenditure, etc.). Finance from the public budget is provided primarily in the form of the state commission: approximately 80 % of public funding over the period 1995 - 2004. Both public and private institutions receive funding through the state commission. However, private institutions are allocated a very small number of state commissioned places, in a restricted range of disciplines. In some cases, this allocation occurs in areas where supply by public institutions is deemed lacking, while in other cases it is intended to reflect public recognition of the quality of the programs.

Both public and private institutions gain income for their teaching activities from student union fees. Public institutions may charge tuition fees to students, who do not gain access to state-commissioned places and, are free to set the level of fees. The one restriction on public universities is that they may mot increase fees by more than 10 % each year.

Students in Estonia fall into one of two distinct groups. Either they occupy state-commissioned places and pay nothing for their tuition or they do not and pay the full costs of their tuition. A third group is emerging: students admitted free of charge at the expense of tertiary institutions. This trend is especially visible at the PhD level.

State-commissioned places are allocated by higher education institutions to students studying full-time on the basis of academic performance. Places are allocated to commencing students on the basis of their performance in relevant entrance exams (essentially the state exams at the end of secondary school). Should a student in a state-commissioned place fail to meet the requirements of full-time study he or she loses the right to occupy such a place and may be replaced by a better performing student undertaking study at the same level. The tuition fees paid by students in fee-paying places vary by type of course and institution.

Quality assurance, inspection and accreditation

Schools and post-secondary

The major act regulating schools providing general education is Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act, which has been changed almost every year since it was passed in the Riigikogu in 1993. The act is mainly consisting of authority tools providing municipalities and schools with autonomy in different aspects of organizing basic and upper secondary schools in Estonia. It also divides the responsibilities for funding matters and regulates different requirements or states who and where regulates different requirements for students and their parents, teachers and management of school, municipalities and other involved bodies.

There have been two major regulations directed to the quality of general education that have been imposed on the system in last decade. The first one is downsizing the maximum number of students in the class and the second one is setting the qualification requirements for teachers. The upper limit of class size for 1-9th grade was changed in 2004 from 36 to 24. The second important regulation concerns the qualification requirements for teachers. Since the deficit of qualified teachers is an important issue in rural areas, which tend to be poorer as well, it is commonly believed that the students in these areas are most disadvantaged. The teacher qualification requirements were set by the regulation of the Minister of Education in 2002.

Estonia has participated in several international comparative studies, e.g. the PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) survey comparing the academic performance of students was conducted in Estonian schools by the OECD for the first time in April 2006. According to average performance, Estonian pupils ranked fifth on the science scale after Finland, Hong Kong (China), Canada and Taiwan (China), in reading they ranked thirteenth and in mathematics they were fourteenth. According to the percentage of pupils at each proficiency level on the science scale, Estonian pupils ranked second after Finland, twelfth in reading and ninth in mathematics.

Higher education

(mainly sourced from: OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education – Country Background Report for Estonia.)

The growth of the system has led Estonian society to the realisation that the quality of higher education varies both by the type of institution and by field of study. Estonia started to build its national quality assurance system in the mid 1990s, in answer to the rapid expansion of the higher education sector. Its goals were to increase the information on higher education offerings and to provide the academic community with support for selfimprovement

Since 1996, by governmental decree, the Standard of Higher Education regulates the establishment of higher education institutions and determines the requirements they and their programmes must meet in order to obtain an education license. This licensing process is carried out by the Ministry of Education and Research.

Quality assurance arrangements are based on an accreditation scheme, which is voluntary but essential both for having the right to issue officially recognised higher education credentials and to have access to state funding. Evaluation is the responsibility of the Higher Education Quality Assessment

Council (HEQAC), established in 1995 and composed of twelve members, appointed by the government on the recommendation of the Ministry of Education and Research (which takes into account the proposal of higher education institutions, academic unions and employers).

HEQAC determines the quality standards, organises external reviews and makes a recommendation to the Ministry regarding universities, professionally- or vocationally-oriented higher education institutions and their operation. The accreditation decision belongs to the Ministry, which normally approves the

recommendation of the HEQAC; however, it can reject it, in which case a new review must be carried out.

The Ministry of Education and Research’s Strategy for Higher Education 2006 - 2015 places a strong emphasis on quality and the means to assure it. Its objectives focus on the competitive quality of Estonian higher education and the need for it to serve the country’s development interests and innovation. Consistent with these objectives, the actions highlight the need to strengthen quality assurance by promoting internal assessment and improvement strategies within educational institutions and establishing quality requirements and supervision of quality by the state.

Estonian information society

(mainly sourced from: ICT Infrastructure and E-readiness Assessment Report: ESTONIA. and Estonian Information Society Strategy 2013.)

When regaining independence in August 1991, Estonia was a relatively backward country technologically. State infrastructure (institutions and people) had to be built up almost from scratch, monetary reform in 1992 established the stable currency. Heavy industry machinery and infrastructure established during the Soviet era found almost no use after the privatization and technological upgrading by the new owners. The access to Russian market was increasingly more difficult due to the politically set trade barriers by the Russian Federation, and the quality of Estonian products was not good enough to compete in the Western markets.

In spite of these unfavorable conditions, Estonian industrial structure started to depart from the factor-driven stage into the investment-driven economy in the early 1990s. The main reasons behind this development most probably were (1) the proximity of technologically advanced Finland and Sweden, (2) large amount of foreign direct investments into Estonian companies, (3) a population with high level of technical education (in the Soviet era, only hard sciences were ideologically free), and (4) a large part of the population ready to consume and adopt modern technology as a part of one’s lifestyle. Additionally, the number of computer and Internet users in Estonia was growing heavily. In recent years, also ICT equipment and services have become much more affordable.

So in light of all these developments, what have been the crucial factors supporting the development of Estonian information society and the growth of ICT centered activities both in public and private sector? According to Krull, 1) building up modern infrastructure; 2) Tiger’s Leap Project in computerizing schools and universities; 3) adopting regulations for information society; 4) government IT-programs; 5) collaboration between the government, private sector and non-governmental initiatives; and last but not least 6) luck have been these main drivers.

In the educational sector, the Tiger Leap program has played an important role in the virtuous circle of making IT popular first among children and through them among the whole society. Almost all children (93 %) have access to the Internet either at school, in the neighborhood or at home. Pupils use the Internet mainly at school (79%). In 2000, there were no basic or upper secondary schools without computers in Estonia, 75% of schools also had online Internet connections.

Additionally, the overall impact of governmental actions has been crucial in the development of Estonian information society. From creating favorable legal environment and leading the way with computerizing the whole public administration, some of the major e-services for the public sector were also developed. Principles for the development of the information society in Estonia were first set out in 1998. However, the first strategic document was established only in 2006.

In Estonia, the development of the information society is, indeed, based on the Principles of Estonian Information Policy, adopted by the Estonian Parliament in 1998. A follow-up to the document, the Principles of Estonian Information Policy 2004 – 2006, was elaborated and approved by the Government of the Republic in 2004. The Estonian Information Society Strategy 2013, in turn, entered into force in January 2007. It is a sectoral development plan, setting out the general framework, objectives and respective action fields for the broad employment of ICT in the development of knowledge-based economy and society in Estonia in 2007 – 2013.

Estonian developments to the direction of information society have been adequate concerning the initiatives started by the public sector. The level and quality of ICT infrastructure and the access to it has gone through a major improvement during the last decade. The role of ICT in the society and Internet’s growing role in providing information, business transactions, interaction between the state and citizens allows to assume that the e-readiness of Estonia is improving with every essential application and service delivered through the Internet. An emphasis made on computerizing the schools and providing vocational education to grownups has been essential.

ICT in education initiatives

Open Estonia Foundation

The Open Estonia Foundation (OEF), a charitable foundation established in 1990 with the help and funding of Georg Soros, made a remarkable contribution to eLearning especially in the early stages during the 1990s. OEF funded several extensive educational projects promoting ICT infrastructure in schools and universities as well as teacher training with a budget of about € 300,000.

Today however, the main responsibility of implementation of services for eLearning is in the hands of non-profit organisations – Estonian Information Technology Foundation and Tiger Leap Foundation. The activities of both institutions are based on special programs with respective budgets.

Estonian Information Technology Foundation

Estonian Information Technology Foundation (EITSA) is a non-profit organization founded by the Estonian Republic, University of Tartu, Tallinn University of Technology, Eesti Telekom and the Association of Estonian Information Technology and Telecommunications Companies. The 5-member Council of EITSA is made up of the representatives of the aforementioned founders. They appoint the 3 members of the Executive Board. The Foundation is annually audited by a sworn auditor.

EITSA's aims are to assist in preparation of the highly qualified IT specialists and to support ICT-related development in Estonia. For these purposes the Foundation established and manages the Estonian IT College, administers the National Support Program for ICT in Higher Education "Tiger University" and coordinates the activities of the Estonian e-Learning Development Centre

Estonian e-Learning Development Centre

(sourced from Estonian e-Learning Development Centre)

The Estonian e-Learning Development Centre (ELDC) operates as a department under the umbrella of the Estonian Information Technology Foundation and coordinates the activities of two consortia – Estonian e-University and Estonian e-Vet. The main objectives of these two consortia are to instigate and facilitate cooperation in universities and vocational schools respectively, to implement e-learning solutions and support e-learning related activities based on the principles of lifelong learning. ELDC was also responsible for porting process of the Creative Commons licenses in Estonia.

In year 2010, the virtual learning environments managed centrally by the ELDC included some 5500 courses with approximately 120 000 unique people enrolled in different e-courses, most of them being university students. Most courses were in Estonian, with the exception of a few English courses. There are still no curricula that one could study fully via the internet.

Estonian e-University

(mainly sourced from: Estonian e-University and The UNIVe Project)

The Estonian e-University (EeU) was officially founded in February 2003. The EeU is a consortium of universities and applied universities and it consists of (as of 2012):

- Estonian Ministry of Education and Research

- Estonian Information Technology Foundation

- University of Tartu

- Tallinn University of Technology

- Tallinn University

- Estonian University of Life Sciences

- Estonian Business School

- Estonian Information Technology College

- Estonian Academy of Arts

The Estonian e-University is a member of EIfEL, EFQUEL, and EDEN. Its main functions are:

- increasing the availability of quality education for students and other people willing to learn, for example adults, handicapped people, Estonians abroad and foreign students,

- educating lecturers of universities to compile and practice quality and efficient e-courses,

- providing lecturers with necessary technical equipment, as well as improving the reputation of university education in Estonia and creating contacts for cooperation between foreign universities and business circles.

Estonian e-Vocational School

The Estonian e-Vocational School was founded in 2005 in cooperation of six professional education institutions, 31 vocational education institutions, the Ministry of Education and Research and the Estonian Information Technology Foundation to promote lifelong learning under the principles of regional development and in the framework of ten thematic networks. It functions under the Estonian e-Learning Development Centre and is financed by the membership fees, the state budget and by Measure 1.1 of the EU’s Social Fund.

Together with the Estonian e-University, it is one of the two main consortia of EITSA. The e-Vocational School consortium accounts for 68 % of the total number of students of the e-Learning Development Center member schools.

Tiger University Program

The Nations Support Program for the ICT in Higher Education "Tiger University" was approved by the Estonian Government in January 2002. Its administration was delegated to the Estonian Information Technology Foundation.

The Tiger University Program goals are to:

- Support for the development of the ICT infrastructure at higher educational establishments,

- Support for the development of ICT academic staff and degree courses' infrastructure.

The priorities are:

- development of ICT infrastructure (upgrading the academic backbones and networks, PC procurements, equipping the labs, providing software),

- development of ICT-related curricula (new curricula, creation of study materials, e-University, e-learning, literature and electronic resources),

- motivating the academic staff (mentoring PhD students, academic sabbaticals, lecturers' and PhD students mobility scheme, internships, visiting lecturers).

Program Council has been set up to coordinate and run the program. Together with the staff it announces the competitions, appoints experts, reviews submissions, is authorised to make allocations, and later monitors and follows up on the results.

University of Tartu

The University of Tartu is said to have been the alma mater for the entire educational system and the scientific research in Estonia. It was founded already in 1632. However, it became a national university - Tartu Ülikool - only in 1919. Nowadays, the university has some 11 faculties, 3 reasearch institutes and 6 colleges with more than 70 departments, institutes and clinics. The number of students is over 18,000 and the number of teaching staff some 1,300.

Open University

The Open University was established in 1996. The mission of the Open University was:

- to improve access to education;

- to diversify study opportunities;

- to make the education more student-centred, taking the student's needs into greater account;

- to provide high quality education under maximum flexibility, with course offerings being independent of time and place.

Today the Open University is a successful hallmark of the University of Tartu, covering both degree education and continuing education programs through distance education or other "unconventional" learning environments. Training under the trademark of Open University is provided by the faculties and colleges at University of Tartu. The activities, in turn, are coordinated by the Open University Centre and the Academic Affairs Office.

Tallinn University

Tallinn University is the third largest university in Estonia, consisting of 18 institutes and 4 colleges. It has more than 8,500 students as well as more than 400 faculty members and research fellows. It is the fastest growing university in Estonia.

Tallinn University, like any other public university in Estonia, uses the 3+2 system (i.e. three years of bachelor studies + two years of master studies). There are 49 specialist areas at the bachelor level, 70 at the master level and 12 at the doctoral level. The university and its curricula have been accredited by the Estonian Higher Education Quality Assessment Council.

The university’s programs are unique in Estonia for the high degree of academic freedom they allow. One quarter to one third of the subjects at every level are freely available and a significant number of specialist subjects are also included as electives. Thus, students are able to design their own study plan quite independently.

Tallinn University is one of the main providers of web-based courses in Estonia. It has a great role in developing LMSs, CMSs and ICT-supported learning methodology. Tallinn University has also developed teachers’ support system in the field of web-based learning and several digital learning materials for general schools.

Tallinn Virtual University

Tallinn Virtual University is a new initiative at the Tallinn University. It was opened in December 2008 and its aim is to make recordings of different open lectures, interviews with lecturers and university visitors, materials of seminars, summer schools, conferences among other things available to everyone. The materials can be watched online or downloaded to one's computer. The Web environment of Tallinn Virtual University is based on Toru technology and it is administered by Nagi OÜ. All videos are located in the Toru video site and can also be found through Toru search.

Tallinn University of Technology

Founded in 1918 as an engineering college (university status was granted in 1936), Tallinn University of Technology (TUT) has now become one of the largest universities in Estonia.

The University is structured into eight faculties, three colleges and six research and development institutions. The faculties are: Civil Engineering, Power Engineering, Humanities, Information Technology, Chemical and Materials Technology, Economics and Business Administration, Science and Mechanical Engineering. The application oriented bachelor-level programs in different technical and economic fields of study are offered in the three colleges - Business College, Kuressaare College and Virumaa College.

TUT has over 13,000 students and personnel of 1,970 (incl. affiliated institutions). Instruction is conducted in Estonian, however, during the first two years, Russian-based general studies are also possible. Selected courses are delivered in English. Tallinn University of Technology is also one of the main providers of ICT education in Estonia. The share of e-courses within total courses is aimed at 15 % in 2010 (4 % in 2005).

Virtual initiatives in schools and post-secondary

Tiger Leap Foundation

(mainly sourced from: Tiger Leap Foundation)

The Tiger Leap Foundation (TLF) has been the initiator and funder of several research activities on ICT in education since 1997. The mission of the foundation is to help to improve the quality of education in Estonia through application of ICT. Focusing mainly on three areas – computers and internet connections for schools, educational software development and teacher in-service training - TLF has been the main driving force of change in Estonian schools. With the help of TLF, all schools in Estonia are connected to the Internet and have original educational software available for most subjects, 75 % of teachers have been trained twice in ICT skills. The foundation also operates the Estonian Schoolnet website www.koolielu.ee.

Since 2004, Tiger Leap Foundation, a partner in the European Schoolnet, is coordinating and funding several EC educational programs: eTwinning, Springday Europe and Netdays Europe among others. New challenges for the foundation are promoting design and technology as well as media studies in Estonian schools. TLF is a non-profit organisation funded by the Estonian Ministry of Education and sponsors.

Audentes e-Gymnasium

The e-gymnasium is part of Audentes Private School and provides its enrolled learners the possibility to cover the secondary education curricula in a blended format with 16-20 hours of contact hours per month. The e-gymnasium uses Moodle as its e-learning platform. The curricula is divided into "subjects > topics > lessons", where each lesson chunk provides learner an activity for about 20 minutes.

Lessons learnt

General lessons

Notable practices

References

- Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (2006)

- OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education – Country Background Report for Estonia.

- Krull Andre (2003)

- ICT Infrastructure and E-readiness Assessment Report: ESTONIA

- Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications (2003)

- Estonian Information Society Strategy 2013

- The Development of e-Services in an Enlarged EU: e-Learning in Estonia. JRC Scientific and Technical Reports, PDF - 125 pages.

- E-learning Development Center - Strategy 2007-2012. Estonian Information Technology Foundation, PDF - 32 pages.

Relevant websites

- Estonian Information Technology Foundation

- Estonian e-Learning Development Centre

- Estonian Information Society in Facts and Figures

- The Estonia Page

- MegaTrends in E-Learning Provision

- Open Estonia Foundation

- Tallinn University

- Tallinn University of Technology

- Tallinn Virtual University

- Tiger Leap Foundation

- The UNIVe Project

- University of Tartu

- Wikipedia

- Eurydice National system overview on education systems in Europe, September 2011

- Eurybase, The Information Database on Education Systems in Europe: The Education System in Estonia, 2009/10

For OER policies and projects in Estonia see Estonia/OER