Welcome to the Virtual Education Wiki ~ Open Education Wiki

Netherlands

by authorname authorsurname

Experts situated in Country

Country in a nutshell

The Netherlands (Dutch: Nederland) is the European part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, which consists of the Netherlands, the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba in the Caribbean. The Netherlands is a parliamentary democratic constitutional monarchy, located in Western Europe. It is bordered by the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east.

The Netherlands is often called Holland. This is formally incorrect as North and South Holland in the western Netherlands are only two of the country's twelve provinces. Still, many Dutch people colloquially refer to their country as Holland in this way, as a synecdoche.

The Netherlands is a geographically low-lying and the 25th most densely populated country in the world, with 395 inhabitants per square kilometre (1,023 sq mi)—or 484 people per square kilometre (1,254/sq mi) if only the land area is counted, since 18.4% is water. The population in total is 16.3 million.

The Netherlands has an international outlook; among other affiliations the country is a founding member of the European Union (EU), NATO, the OECD, and has signed the Kyoto protocol. Along with Belgium and Luxembourg, the Netherlands is one of three member nations of the Benelux economic union. The country is host to five international (ised) courts: the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, the International Criminal Court and the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. All of these courts (except the Special Tribunal for Lebanon), as well as the EU's criminal intelligence agency (Europol), are situated in The Hague, which has led to the city being referred to as "the world's legal capital."

Education in Country

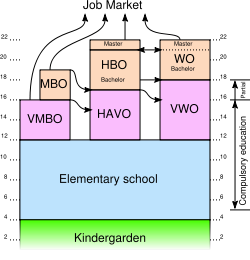

Compulsory education (leerplicht) in the Netherlands starts at the age of five, although in practice, most schools accept children from the age of four. From the age of sixteen there is a partial compulsory education (partiële leerplicht), meaning a pupil must attend some form of education for at least two days a week. Compulsory education ends for pupils age eighteen and up.

Basisonderwijs - Primary education

Between the ages of four to twelve, children attend basisschool (elementary school; literally, "basis school"). This school has eight grades, called groep 1 (group 1) through groep 8. School attendance is compulsory from group 2 (at age five), but almost all children commence school at four (in group 1).

Voortgezet Onderwijs - Secondary Education

On leaving primary school basisonderwijs at the age of about 12 (after eight years of primary schooling) children choose between three types of secondary education (voortgezet nderwijs) :

- VMBO (pre-vocational secondary education voorbereidend middelbaar beroepsonderwijs: four years)

- HAVO (senior general secondary education hoger algemeen voortgezet onderwijs: five years)

- VWO (preuniversity education voorbereidend wetenschappelijk onderwijs: six years).

Most secondary schools are combined schools offering several types of secondary education so that pupils can transfer easily from one type to another. All three types of secondary education distinguish between the lower years and the upper years. In the lower years the emphasis is on acquiring and applying knowledge and skills, and delivering an integrated curriculum. Teaching is based on attainment targets which specify the knowledge and skills pupils must acquire. In the first two years of secondary school, 1,425 real hours per year must be spent on the 58 attainment targets. The school itself translates these targets into subjects, projects, areas of learning, and combinations of all three, or into competence-based teaching, for example. Besides English, which is compulsory for all pupils, those in HAVO and VWO study two other modern languages, while pupils in VMBO study one.

VMBO There are four learning pathways in VMBO:

- basic vocational programme;

- middle-management vocational programme;

- combined programme;

- theoretical programme.

After completing VMBO at the age of around 16, pupils can go on to secondary vocational education (MBO). Pupils who have successfully completed the theoretical programme within VMBO can also go on to HAVO. HAVO certificate-holders and VWO certificate-holders can opt at the ages of around 17 and 18 respectively to go on to higher education.

HAVO is designed to prepare pupils for higher professional education hoger beroepsonderwijs (HBO). In practice, however, many HAVO school-leavers also go on to the upper years of VWO and to secondary vocational education middelbaar beroepsonderwijs.

VWO is designed to prepare pupils for university. In practice, many VWO certificate-holders enter HBO. MBO certificate-holders can go on to higher professional education, while HBO graduates may also go on to university.

In addition to mainstream primary basisonderwijs and secondary schools voortgezet onderwijs there are special schools speciaal onderwijs for children with learning and behavioural difficulties who – temporarily at least – require special educational treatment. There are also separate schools for children with disabilities of such a kind that they cannot be adequately catered for in mainstream schools. Pupils who are unable to obtain a VMBO qualification, even with long-term extra help, can receive practical trainingpraktijkonderwijs, which prepares them for entering the labour market.

Young people aged 18 or over can take adult education courses or higher distance learning courses.

Vervolgonderwijs

Mbo (middelbaar beroepsonderwijs, literally, "middle-level vocational education") is oriented towards vocational training. Many pupils with a vmbo-diploma attend mbo. Mbo lasts three to four years. After mbo, pupils can enroll in hbo or enter the job market.

Hbo With an mbo, havo or vwo diploma, pupils can enroll in hbo (Hoger Beroeps Onderwijs, literally "higher professional education"). It is oriented towards higher learning and professional training, which takes four to six years. The teaching in the hbo is standardized as a result of the Bologna process. After obtaining enough credits (ECTS) pupils will receive a 4 years (professional) Bachelor's degree. They can choose to study longer and obtain a (professional) Master's degree in 1 or 2 years.

Wo With a vwo-diploma or a propedeuse in hbo, pupils can enroll in wo (wetenschappelijk onderwijs, literally "scientific education"). Wo is only taught at a university. It is oriented towards higher learning in the arts or sciences. The teaching in the wo, too, is standardized due to the Bologna process. After obtaining enough credits (ECTS), pupils will receive a Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science or Bachelor of Laws degree. They can choose to study longer in order to obtain a Master's degree of different fields. At the moment, there are three variants: Master of Arts, Sciences, and Master of Laws. A theoretical Master typically lasts one year, however the majority of practical (e.g. medical), technical and research Masters require two or three years.

Schools in Country

Further and Higher education

There are two types of higher education in the Netherlands (see also above). The universities prepare students for independent scientific and scholarly work in an academic or professional setting. The hogescholen are universities of applied sciences that prepare students for a wide variety of careers in seven sectors: agriculture, engineering and technology, economics and business administration, health care, education/teacher training, social welfare, and fine and performing arts. This type of higher education is known in Dutch as HBO (hoger beroepsonderwijs). At present there are 14 universities in the Netherlands and 45 universities of applied sciences.

The differences between the universities of applied sciences and the research universities have become less marked in the course of time. Nevertheless, a number of differences remain. Universities of applied sciences offer four-year programmes, leading to a Bachelor's degree, which are strongly geared towards practical training. The programmes focus on specific occupations and include traineeships or work placements that provide students with practical work experience. Universities of applied sciences also offer an increasing number of programmes that lead to a Master's degree.

Universities in Country

Polytechnics in Country

Colleges in Country

Education reform

Schools

Post-secondary

Administration and finance

Schools

Education policy is coordinated by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, together with municipal governments. A distinctive feature of the Dutch education system is the combination of a centralised education policy with decentralised administration and management of schools. In August 2006 the government introduced block grant funding in primary education in order to give schools more freedom in terms of spending. School boards have been given a certain budget and the freedom to decide on the spending. For secondary education block grant funding was introduced in 1996.

Central government controls education by means of regulations and legislation, taking due account of the provisions of the Constitution. Its prime responsibilities with regard to education relate to the structuring and funding of the system, the management of public-authority institutions, inspection, examinations and student support. Central government also promotes innovation in education. The Minister is, moreover, responsible for the coordination of science policy, emancipation policy of women and gays and for cultural and media policy. There are public, special (religious), and private schools. The first two are government-financed and officially free of charge, though schools may ask for a parental contribution (ouderbijdrage). Public schools are controlled by local governments. Special schools are controlled by a school board. Special schools are typically based on a particular religion. There are government financed Catholic and Protestant elementary schools, high schools, and universities, furthermore there are government financed Jewish and Muslim elementary schools and high schools. In principle a special school can refuse the admission of a pupil if the parents indicate disagreement with the school's educational philosophy. This is an uncommon occurrence. Practically there is little difference between special schools and public schools, except in traditionally religious areas like Zeeland and the Veluwe (around Apeldoorn). Private schools do not receive financial support from the government. There is also a considerable number of publicly financed schools which are based on a particular educational philosophy, for instance the Montessori Method, Pestalozzi Plan, Dalton Plan or Jena Plan. Most of these are public schools, but some special schools also base themselves on any of these educational philosophies.

Post-secondary

Quality assurance

Schools

In the Netherlands the Education Inspectorate (Onderwijsinspectie) is responsible for supervising the education system as a whole and the performance of the individual schools and educational institutions. All institutions in primary, secondary and special education, as well as in vocational and adult education are regularly visited and evaluated. The inspectorate applies the same standards for schools with a public board and schools with a private board, the latter of which are the vast majority in the Netherlands. The basis for the supervision is a rating framework consisting of the thirteen quality aspects named in the Education Supervision Act and the attached indicators and points of attention ( see https://www.onderwijsinspectie.nl). The use of ICT is integrated within these indicators. These frameworks are set up in consultation with representatives of the education sector and require the approval of the Minister of Education (article 12 of the above-mentioned Act). A distinction is made between quality aspects that concern the results of the education provided and those that concern the teaching-learning process. Within the framework, indicators are designated that measure the core elements of education quality. These “key indicators” form the basic set for the so called Periodic Quality Assessment (PQA). This model of supervision is conducted once every four years at all educational institutions. Under the Education Inspection Act the duties of the Inspectorate are:

- to assess the quality of teaching on the basis of checks on compliance with legislation;

- to monitor compliance with legislation;

- to promote the quality of teaching;

- to report on the development of education;

- to perform all other tasks and duties required by law.

Under the Primary Education Act (WPO), the Secondary Education Act (WVO) and the Adult and Vocational Education Act (WEB), school boards bear primary responsibility for ensuring the quality of teaching. As the competent authority, they are the point of contact for inspections. Wherever possible, risk analyses are conducted on the basis of existing information. The Inspectorate will not ask for supplementary information unless risks are identified and a further inspection is considered necessary. A report of the Inspectorate’s findings is sent to the school or institution concerned, to the Minister and State Secretaries, and to parliament.

Quality assurance in ICT integration in schools

The Ministry of Education regards monitoring the development of ICT in education as very important and requires this process to be conducted annually. AN annual ICT monitor is carried out by Kennisnet, the dutch foundation which supports school in primary, secondary and vocational education in integrating ICT in their school policies The monitor collects data on key factors or indicators that are known to influence the efficient and effective use of ICT in education. The conceptual framework for the monitor is derived from the so-called Four in Balance model, which reflects a research-based vision of the introduction and the use of ICT in education. The core premise underlying the Four in Balance model is that use of ICT for educational purposes in schools depends on maintaining a balance between four building blocks:

- the vision relating to education and ICT;

- knowledge and skills of teachers;

- educational software (including content);

- ICT infrastructure.

Data for this monitor are collected from a representative sample of school boards, school management, teachers and students by both the Dutch inspectorate for education and several research institute.

The latest report published by Kennisnet is the Four in Balance Monitor Report 2010

Post-secondary

Information society

In the Netherlands, access to online information is not only supported by a high diffusion of internet connections, but also by many organisations, businesses and (increasingly) citizens providing online content. Moreover, the Dutch government contributes to a high quality of available information, supports the European Safer Internet Programme and is in favour of net neutrality, the principle of letting all internet traffic flow equally and impartially, without discrimination.

The government bears some responsibility for internet safety, taking a leading role compared to industry and schools. In 2008 the government, in collaboration with business, started the programme Digivaardig & Digibewust, the Dutch programme promoting e‑awareness, e‑inclusion and e‑skills. This programme aims at the e‑inclusion of all Dutch people by promoting safe internet use and media literacy.

In line with the liberal values in Dutch society the government is committed to the freedom of expression in the online environment, as elsewhere, as long as these expressions stay within the limits of what is legally acceptable (see the section on the legislative environment below). This also holds for the protection of privacy on the net. Although there is fairly little concern among citizens about threats to their privacy, the data protection law is available to penalise the abuse of personal information.

The Dutch government is seeking to use ICT tools to reduce administrative burdens and improve service delivery. Internationally, the Netherlands is at the forefront in these tasks. In line with the traditional Dutch focus on participative and inclusive government, featuring broad citizen consultation and involvement, the Netherlands has developed ambitious programmes and activities that aim to increase user take-up of e‑services.[7] In order for citizens to reach a fast, efficient and customer-focused government, policy is directed towards the development of a basic infrastructure, which includes electronic access to the government, e‑authentication, basic registration and services (e.g., applying for a passport). However, the take-up of e‑services is rather slow, partly due to insufficient skills of the Dutch, and also due to a lack of user orientation in e‑government services.[

A strong new trend is the rise of Web 2.0, leading to a substantive deepening of existing internet use and means that people will begin making use of various kinds of different content. Because the content created by users is not constrained to textual information, audiovisual information is added in increasing amounts to the web as music and self-made film clips are shared with others. In the Netherlands the social networking site Hyves has attracted many people, in particular the youth. As is the case elsewhere in the world, Twitter is the latest fashion in information exchange.

Web 2.0 also creates opportunities for musicians and other artists to offer (trailers of) their music and other forms of creative expression on the net. MySpace is currently a popular website in the Netherlands, where large numbers of users maintain weblogs and profiles.

Another but related trend is the improvement of media literacy. In the Netherlands media literacy is often called “media wisdom”, which refers to the skills, attitudes and mentality that citizens and organisations need to be aware, critical and active in a highly mediatised world. Most Dutch media education initiatives are directed at the internet and audiovisual media. However, the converging of different media platforms makes it hard to distinguish separate media. TV, mobile and internet are converging, and virtual worlds and “real” worlds also seem to be merging.

Action steps

Some of the main issues that need special attention in the future are:

- Media literacy: In October 2006 the Dutch cabinet stressed the importance of this topic and saw the need for a centre of media expertise and a code of conduct for the media. The centre was established in May 2008. Many different organisations are involved in activities that aim to achieve the goal of increasing media literacy.

- Identity management: Due to a combination of technological and social developments we can see an increasing convergence of new technologies and services. Steps need to be taken in order to support the identity management of citizens and to increase their sense of online security.

- Improved internet safety: Cyber bullying, cyber crime (hacking, phishing, viruses, etc.) and inappropriate and illegal content are prolific. Good organisations and campaigns have already been established. However, this is an ongoing task and there is still work to be done.

sourced from Access to online information and knowledge 2009, country report on the Netherlands