Welcome to the Virtual Education Wiki ~ Open Education Wiki

Sweden from Re.ViCa: Difference between revisions

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

==Swedish HEIs in the information society== | ==Swedish HEIs in the information society== | ||

NB: | source: Holmberg Carl (2003) | ||

On the Move Towards Online Education in Sweden. NKI Förlaget – Online Education and Learning Management Systems by Morten Flate Paulsen. | |||

(NB: UNDER CONSTRUCTION) | |||

===A country online=== | ===A country online=== | ||

Revision as of 12:44, 4 September 2008

Sweden in a nutshell

Sweden, officially the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Area-wise, it is one of the largest countries in Europe. Its population is around 9 million or on average 20 inhabitants per square kilometer. The population is very unevenly distributed: some 84 % live in urban areas, and about one third in the 3 major cities of Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö.

Sweden is a constitutional monarchy (parliamentary democracy). It has been a member of the European Union since 1995, but it has not joined the European Monetary Union. The capital and largest city is Stockholm, with a population of around 800,000 and metropolitan area of 2 million. The official language is Swedish.

Swedish education policy

Sweden has a strong social-democratic tradition which stresses the redistributive role of state, social inclusion and equality, underpinned by high levels of taxation and public spending. The education system is an integral component of the Swedish concept of the welfare state, and the Swedish spending on education is, indeed, amongst the highest in the world.

Swedish education system

The Swedish education system consists of a compulsory comprehensive nine-year school, a three-year upper-secondary school with pre-academic as well as vocational programs, and a unitary higher education sector that includes academic, professional and vocational programs. There is also a specific sector, the folk high schools, that provides adult education at all levels, ranging from basic school qualifications to vocational programs, some of which can be described as offering an alternative to higher education.

Additionally, municipal adult education offers education at compulsory and upper-secondary school level for those lacking these qualifications as well as vocational training for adults. Advanced Vocational Education is a form of vocational post-secondary education designed and carried out in close co-operation between enterprises and course providers (higher education, upper-secondary schools, municipal adult education and companies).

Equal access to education has long been one of the pillars of the Swedish welfare state. Education from primary school to higher education is mainly tax financed and free of charge to the student. The main distinguishing feature of HE from other forms of education is that HE is based on science or art and on tested experience.

Higher education in Sweden

Swedish tertiary education is provided mainly in the higher education sector, which comprises universities and university colleges. Today, there are 14 state universities, 22 state university colleges, 3 private institutions with undergraduate as well as postgraduate education, and a number of smaller private institutions. The HEIs range from large multi-faculty institutions to specialized institutions of different sizes.

In 1977, the Swedish system was transformed from a binary system of higher education to a formally unitary one comprising academic, vocational and longer and shorter professional programs. In the later part of the 20th and early 21st century higher education has expanded significantly and new institutions have been founded throughout Sweden. The last 15 years have seen a large increase in the number of students as well.

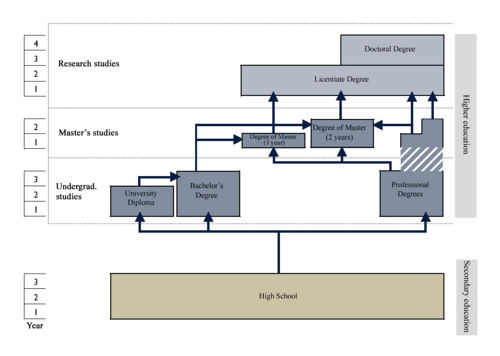

In academic year 2007 – 2008, the Swedish HEIs adopted a new degree structure that conforms to the Bologna Process. The new degree structure creates three levels of higher education – a first level, second level, and third level – each with minimum requirements for entry (see picture 4). Degrees awarded at each level are defined in terms of the expected results and abilities of students. Sweden has also introduced a new credit system, which is compatible with the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS). Under the new system, one academic year of full-time studies is equivalent to 60 higher education credits.

First level

At the first level of study, there are two degree options: the University Diploma, achievable after two years of study (120 ECTS), and the Bachelor's Degree, achievable after three years (180 ECTS). One prerequisite for starting higher education studies at the first level is the successful completion of an upper secondary school education.

Second level

At the second level of study, there are also two degree options:

- There is a new two-year master’s degree - Degree of Master (Two Years) (120 ECTS). Authorization to award the Degree of Master is given to state universities and other higher education institutions that are approved for research in one or more disciplinary domains, and to private education providers that are authorized to award doctorates and licentiates in a disciplinary domain. Other higher education institutions have to apply to the Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (state education providers) or the Government (private education providers) for authorization to award the degree.

- The Degree of Master (One Year) (60 ECTS) is limited to one-year study programs only.

A prerequisite for studying at the second level is the completion of at least three years at first level at a Swedish higher education institution, or the international equivalent – such as a three-year bachelor’s degree (180 higher education credits). Specialized knowledge may also suffice.

Third level

At the third level of study, students are eligible for a Licentiate Degree after two years of research (120 ECTS), and a Doctoral Degree (PhD) after fours years of research (240 ECTS). A prerequisite for studies at the third level is possession of a second-level degree – a Degree of Master (Two Years) or a Degree of Master (One Year) – or the completion of four years of full-time studies – three at the first level and at least one year at the second level. Comparable international degrees are also admissible, and specialized knowledge may suffice as well.

Sweden has seen an impressive growth in tertiary qualification over the past generations. Among the younger population (25-34 -year-olds), 37 % hold a university degree in comparison with 25 % among the 55-64 -year-olds. Graduation from traditional universities stands at 37.7 %. Sweden is also one of the European countries, of which graduation rate from advanced research programs (PhD or equivalent) exceeds 2.0 % (Sweden: 2.2%).

The share of international education market is relatively modest for Sweden which receives 1.4 % of all foreign students enrolled in tertiary education. However, Sweden still places itself well ahead of its Nordic neighbors. In 2005, international students comprised 4.4 % of all tertiary enrolment (76 %) in Sweden.

Higher education reform

Administration and finance

Like all other public administration sectors in Sweden, also higher education is subject to management by objectives and results. State higher education institutions in Sweden are formally Government agencies, subject to the same general body of legislation as other agencies, but with a complementary set of sector-specific laws and regulations designed, among other things, to safeguard academic freedom.

Decision making in HE is decentralized, with a relatively high degree of powers and responsibilities having been delegated to the institutions. The Government decides on objectives and specifies the required results, while it is the responsibility of the institutions to ensure that the activities are carried out in the best possible way. There is a substantial amount of freedom for the institutions to decide on the use of their resources and organization of their activities as well as their educational profile. The institutions are required to report back to the Government in various ways.

Higher education and research in Sweden, as a whole, is financed predominantly by public funds, mainly via direct allocations from the state to the institutions. However, the proportion allocated directly in relation to other funding sources differs for undergraduate and graduate studies on the one hand and for research and doctoral studies on the other. In total, over 85% of the revenues for higher education, excluding research and doctoral studies, consist of direct state allocations. The proportion of funding received by the HEI’s for research and doctoral studies from direct state allocations is substantially lower.

Quality assurance

The Swedish National Agency for Higher Education is responsible for the quality evaluation. All programs and major subjects have been evaluated during the six-year period of 2001 – 2007. The Swedish National Agency for Higher Education has also completed two rounds of quality audits of higher education institutions.

Swedish HEIs in the information society

source: Holmberg Carl (2003) On the Move Towards Online Education in Sweden. NKI Förlaget – Online Education and Learning Management Systems by Morten Flate Paulsen. (NB: UNDER CONSTRUCTION)

A country online

As in other countries, investments in information technology have been relatively high over the decades. The use of radio, television, video, and computers in education and training has been investigated and discussed by state commissions one after another, many of them having had money to feed into the education systems for development work. However, the expected outcomes of different initiatives were seldom reached. Ambitious goals of dramatic changes in education systems were not fulfilled. They often proved to be unrealistic in the Swedish context and local innovative projects implementing changes turned out to give only temporary changes. After the project periods one could most often notice a return to the old solutions.

On the other hand, the decades of development work and various committees also had its effect: common awareness and investments in technology infrastructure were increased. A large variety of technical equipment and fast communication networks were also successively installed. A turning point came in the mid 1990s, and some of the main factors behind it were:

- very strong demonstration of official policy on the introduction of IT;

- setting-up of agents for change supporting development of education systems;

- pushes and pulls – more space for local initiatives.

In February 1994, the Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt gave a speech about setting a new political agenda for the transformation of Sweden into a nation drawing upon the resources of information technology. He formed an IT Commission where he himself was a chair and many of the other ministers of his government were delegates. Included in the commission were also researchers and representatives of business and industry. The idea was to initiate, promote and get IT-related transformations in all sectors of society, and the main task for the commission was to highlight the possibilities of IT, to identify limitations and pave the way for the introduction of it. Also an IT policy was developed.

From 1994 onwards, the idea was to invest approximately one billion Swedish crowns (€ 110 million) per year in research and development work. Up till 2003, that most probably also was the case. Altogether development programs, foundations, research schemes, national agencies and authorities, and municipalities some years spent more than that. All in all, the fact that the government itself tried to demonstrate good practice, to be a spearhead in the introduction of IT, was of high importance.

The prosperous future of e-learning

Sweden has been no exception to other countries when it comes to expectations concerning the e-learning market. If anything, commercial hopes have been higher than in other countries. Education systems are looked upon as potent instruments in the change processes in society. Governments in Sweden have, indeed, very actively worked with the agendas for the education systems. During the major part of the 20th century, adult education in various forms also played an important role in the Swedish education system.

When in many other countries open universities were created, Sweden chose not to build a single-mode institution for distance education. Instead an extremely decentralized system was set up for the tertiary level. The responsibility for carrying out distance education rested with the individual university departments, which at the same time organized traditional forms of university education. Thus, a dual-mode system was created. Those decisions during the 1970s about the tertiary level, however, led to a markedly small-scale type of distance education.

At the beginning of 1990s, about 800 distance education courses were arranged. A majority of those courses, however, had either no distance education at all or were courses with just a few distance education elements. No doubt, this confusion was to a great extent due to the extremely decentralized and small-scale organization of distance education at Swedish universities. Small changes over the years were shown, but the state-of-the-art was not at all up to the standards expected by the authorities.

In the academic year 1994 – 1995, the number of students following distance education courses was 25,800, which was an increase of 60 % over a couple of years. It was about 10 % of the student population.

During the 70s, 80s and 90s, the ambitions of the government were to increase the extent of distance education. In the light of history, the actions taken for improving that field can be described as four steps (Umeå University, The University Consortia, Dukom and Distum, Nätuniversitetet), each of which was a trial of alternative strategies.

Umeå University

In the late 1980s, the government made a first large-scale attempt by concentrating funds and efforts on a development program at Umeå University. The overarching purpose was to contribute to rural development in the northern sparsely populated areas of the country. By developing expertise in distance education, Umeå University could be the main actor in the field and a front-runner having followers at other universities. A mild description of the outcome could be that those ambitions were not fulfilled.

The University Consortia

The second step was taken by the government through making resources available to stimulate co-operation between universities. By gathering expertise from different institutional bodies and bringing a diversity of stakeholder perspectives together, new and more potent organizers of distance education could grow. This brought about the establishment of a number of university consortia with the purpose of developing distance education in joint projects. Co-operation between autonomous institutions at tertiary level is known worldwide as a difficult task. Apart from demonstrating that, the consortia had difficulties in building the necessary fundament of knowledge to be efficient producers and deliverers of distance education.

Dukom and Distum

The third step was taken through forming the Commission on Distance Methods within Education. The Minister of Education appointed the Commission during 1995 with the assignment to outline strategies for distance education policy. The major suggestion by the Commission was to set up a new coordinating body for distance education. That institution should have resources to sponsor development work and research. It was to organize a national web site with tools for Distance Teaching and Distance Studies. It was also to inform about research in the field of distance education.

In July 1999, the Swedish Agency for Distance Education (Distum) commenced its operations in Härnösand in the north of Sweden. The agency would promote the development and application of distance education based on information and communication technologies (ICT-based distance education). The operations would encompass universities/colleges and popular public education throughout the country. The major strategy of Distum was to support the development of new knowledge about flexible education at a distance and to disseminate that knowledge to universities and other bodies for adult education. Research and testing of ideas in practice were important tools for Distum. The hypothesis was that with a sound base of new knowledge the educational organizations would make decisions about revised forms for arranging education.

In March 2002, the Ministry of Education and Science closed Distum. A little more than 2.5 years was of course too short a time to test all basic ideas behind Distum’s role as an agent for change. Many different factors were influencing the decision from the Ministry. One important aspect was that the organization found it hard to gain credibility among the institutions for higher education.

Swedish Net University

The fourth route towards a more pluralistic way of teaching and learning at the universities has been tested since 2002, when the Swedish government decided to set up the Swedish Net University. It is based upon the courses and programs already given by the universities and university colleges, of which participation in the Net University is voluntary. In order to support the project, the Swedish Net University Agency was also set up. The primary task of the agency is to co-ordinate the different courses given by various Swedish universities and for that purpose run a web site exposing the courses. The agency also supports improvements in skills and competence among distance education teachers and other personnel and identifies topics and areas that would benefit from more distance education.

Thus, a lot of the initiatives in this fourth step of promoting distance education and its followers have moved back to the institutional level. That together with seed money is the driving force in this case. During the first years of existence, each student taking courses via the Net University gave a much higher return to the university than students following on campus courses. For the first two years, 371 million SEK (€ 41 million) was also spent on this purpose.

Still waiting for online learning

So how come online education is not a more dominating trait in Sweden? A variety of aspects have influenced developments of where the country is today. On the positive side all work so far has created a very good climate for future development of online learning, on the negative side there has been and still is a lack of understanding of the complexity of the change processes needed to support these new forms of teaching and learning.

The situation in Sweden (2003) is that many of the prerequisites for online learning are present. There is a growing digital generation. Not just are growing numbers of youth competent users of the net and computers, but also a very large portion of those who have had to the enter the digital world as grown-ups. The technology infrastructure is, therefore, also advanced.

Digital maturity and infrastructure are, indeed, at hand. So what is missing for online learning to take off? One aspect is money or more correctly the willingness to pay for education. Swedes are not used to paying for education. It is looked upon as a free asset. The universities in Sweden are not allowed to receive payment from students for the provision of higher education. Tertiary education in Sweden is financed by public means. The incentive for Swedish universities to go online and educate foreign students for free is, thus, very limited. Therefore, Swedish universities have neither been active in the international Internet-based education business.

On the other hand, in the Swedish context, it is hard for international competitors to compete, because the national system offers the services for free and it also provides higher education in the native language, Swedish. International competition to recruit students has, therefore, been very low or non-existent in comparison with the situation between the Anglo-Saxon (US, UK, Australia and Canada) global players on other markets.

Additionally, the lack of organizational memory as far as projects in ICT and learning are concerned is somewhat problematic. The wheels are often reinvented due to the lack of holistic views and historical perspectives. Also many of the attempts to develop and commercially introduce online learning have had problems related to lack of competence. In order to succeed, experts from different fields are needed. Especially, knowledge of the target groups and how they live and learn is needed.

Finally, a more profound aspect of the change processes is the understanding of and the compliance with policies developed at the national level. The simple logic behind presenting a ‘good idea’ and having people living in accordance with it is not always there. To what extent the ideas and initiatives from government and central authorities are reflected in policy documents at the HEIs in Sweden? The decentralized education system presupposes that the development is initiated and realized locally. However, local policies are seldom developed.

Virtual initiatives in HE

References

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2007)

- Education at a Glance – OECD Briefing Note for Sweden.

- Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (2006)

- OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education – Country Background Report for Sweden.

- Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (2008)

- The Swedish Higher Education System

Relevant websites